As a drug salesman, Mike Courtney worked hard to make health care expensive. He wined and dined doctors, golfed with them and bought lunch for their entire staffs — all to promote pills often costing thousands of dollars a year.

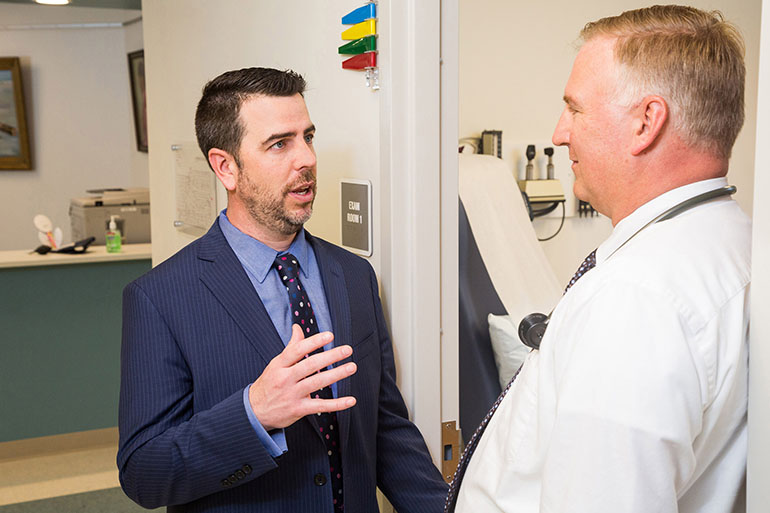

Now he’s on a different mission. When Courtney calls on doctors these days, he champions generic drugs that frequently cost pennies and work just as well as the kinds of pricey brands he used to push.

Instead of big pharma, he works for Capital District Physicians’ Health Plan (CDPHP), an Albany, N.Y., insurer. Instead of maximizing pill profits, his job is to save millions of dollars by educating doctors about expensive prescriptions and the stratagems used to sell them.

“Having come from big pharma, I do really feel my soul has been cleansed,” laughs Courtney, who formerly worked for Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. “I do feel like I’m more in touch with the physicians” and plan members, he added.

Costs for prescription drugs have been rising faster than those for any other health segment, marked by high-profile cases such as the reported 400 percent increase for Mylan’s EpiPen and 5,000 percent spike for Turing Pharmaceuticals’ Daraprim.

Health plans and others paying those costs are fighting back. Many have tried to give doctors academic research on pill effectiveness or simply removed high-cost drugs from coverage lists.

Consumer groups and medical societies have tried to spread the word about expensive drugs. Startup GoodRx lets patients compare retail prices online.

CDPHP is one of the few insurers to have taken the battle against pricey pills a step further. It is recruiting across enemy lines, hiring former pharma representatives and staffing what may be a new job category: a sales force for cost-effective medicine.

“Insurers are taking matters into their own hands,” said Lea Prevel Katsanis, a marketing professor at Canada’s Concordia University who specializes in the pharmaceutical industry. “They’re saying, ‘We can’t really rely on drug companies to talk to doctors about what’s cost-efficient.’”

If insurance companies can curb drug costs, premiums paid by employers, taxpayers and consumers need not rise as fast.

Two years ago, when one company increased the cost of a common diabetes medicine to 20 times what it had been a few years earlier, Courtney and five other former pharma and medical-device reps working for CDPHP knew what to do.

Valeant Pharmaceuticals had cranked up the price of one common dosage of its Glumetza medicine for lowering blood sugar to an astonishing $81,270 a year, according to Truven Health Analytics, a data firm. Meanwhile a similar, generic version can be bought for as little as a penny a pill.

Because Glumetza was on CDPHP’s list of approved drugs, the insurer and its members had to pay for it when doctors prescribed it, resulting in millions in extra costs and stinging copayments for patients.

Dr. Eric Schnakenberg, an upstate New York family medicine doctor, was shocked when patients began complaining about what he assumed was an inexpensive prescription. Doctors are famously unaware about the cost of the care they order, a situation exploited by drug sellers and other vendors.

While physicians’ electronic prescribing programs and even pharmaceutical guides like the Physicians’ Desk Reference contain prescribing information — some are even peppered with ads — they contain no specific information about prices. Drug sales reps who visit their offices don’t highlight high prices as they drop off free samples, and drugmakers can quietly, but substantially, hike the price of a drug from one year to the next.

“As physicians, we’re blindsided by that,” Schnakenberg said. “We get patient complaints saying, ‘Hey, I can’t afford this,’ and we say: ‘It’s cheap!’”

After Courtney and his colleagues alerted doctors to what Valeant was up to, all but a handful of the 60 plan members who were taking Glumetza switched to metformin, the generic alternative. That saved about $5 million in a year.

Following an outcry over its practices, Valeant agreed last year to raise annual prices by no more than single-digit percentages, the company said through a spokesman. But such hikes could still outpace the inflation rate.

Using ‘Those Powers For Good’

Cardiologist John Bennett got the idea to hire pharma reps a few years ago, after he became CDPHP’s chief executive. He knew reps are smart, genial and motivated. Overhiring by pharma had put many back on the job market.

His sales pitch to them, he says half-jokingly, was: “You know everything they taught you in big pharma? How would you like to use those powers for good?”

Pharma companies spend billions on TV ads, doctor blandishments and expensive salespeople to keep prescriptions flowing.

Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson and other sellers responded to critics a few years ago by restricting gifts of entertainment, coffee mugs and some meals. But the industry’s ethics code still allows lavish consulting contracts for doctors and sponsorship of physician conferences as well as meals for doctors and their staffs who listen to an “informational presentation” from sales reps touting expensive pills.

“When those products go generic, nobody’s promoting them anymore,” Courtney said. Generics makers lack big marketing budgets. CDPHP’s remedy: The insurer promotes generics with its own reps.

“It’s a great idea,” said Alan Sorensen, an economist at the University of Wisconsin who has studied drug prices. “Even a small moving of the needle on their [doctors’] prescribing behavior can have a pretty big impact on costs.”

At first the team concentrated on educating doctors about cheaper alternatives to Lipitor, a widely prescribed cholesterol-lowering medicine, and Nexium, for stomach problems. That saved around $10 million the first year, much in the form of copayments that would have been owed by plan members.

Recently the plan has focused on Seroquel, a branded antipsychotic that costs far more than a similar generic. Switching to the generic saves $600 to $1,000 a month, estimates Eileen Wood, the insurer’s vice president of pharmacy and health quality.

CDPHP’s repurposed reps have helped keep the insurer’s annual drug-cost increases to single-digit percentages, whereas without them and other measures “we would certainly be well into double-digit” increases, she said.

Educating doctors about drug costs is part of a larger push for “transparency” in an industry where Princeton economist Uwe Reinhardt says consumers face the same experience as somebody shopping in Macy’s blindfolded.

Current research by the University of Wisconsin’s Sorensen finds physicians with access to data about drug prices and insurance coverage are more likely to prescribe generics.

That gives Courtney and his colleagues a fighting chance, even if, he said, “we don’t have the freewheeling, unlimited green Amex card like I did back in the day.”

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.