From their base in Baltimore, leaders of Johns Hopkins Medicine can see the future – and it’s at the hospital down the road.

From their base in Baltimore, leaders of Johns Hopkins Medicine can see the future – and it’s at the hospital down the road.

The world-class academic medical center is reaching deep into new territory, last year acquiring a hospital in suburban Maryland and now awaiting approval to add Sibley Memorial in the District to its roster of hospitals and clinics.

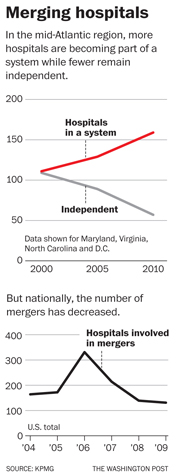

The acquisitions are part of a wave – particularly in the Mid-Atlantic region – of consolidations leading to fewer independent hospitals and doctors, a trend that many industry executives say will only grow because of the health reform law.

The action in the mid-Atlantic is being watched closely, as experts say consolidation in other parts of the country has led to higher health-care prices: Size is power, and commanding market share can give hospitals an edge in negotiations with insurers. That kind of leverage mirrors the advantage many big insurers have, which has prompted complaints from doctors and hospitals. Today, tensions between hospitals and insurers are running high as both face immense pressure to contain costs.

“All the evidence very clearly shows consolidation leads to higher prices,” says Martin Gaynor, an economist at Carnegie Mellon. “Guess who pays for those higher prices? One might think insurers would eat them. No, they don’t. It goes into higher premiums. When premiums go up, employers just pass them right on to their workers, either in the form of lower wages or reduced benefits.”

The Federal Trade Commission found rapidly rising prices in some markets after hospitals joined. For example, such steep increases followed the 2000 merger of two Chicago-area hospitals that in 2008 the FTC forced the two to negotiate with insurers separately.

That same year, the FTC filed a complaint over Fairfax-based Inova Health System’s plan to merge with Prince William Health System, which included a hospital in Manassas, saying the deal would give Inova control of nearly three-quarters of the Northern Virginia market and likely drive up costs for employers, consumers and insurers. The two dropped their plans to merge shortly after and the Prince William system eventually joined with North Carolina’s Novant Health.

Hospital leaders from Baltimore to Seattle say the health law approved by Congress in March gives them even more reason to merge with or buy rivals because of its emphasis on integrated systems where hospitals and doctors better coordinate care.

Also fueling the trend: More doctors want to be employed directly by hospitals, allowing them more job security without the hassles of running a business. But hiring groups of doctors can be an “expensive and daunting proposition” for a stand-alone facility, says Steven Thompson, senior vice president for Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Nationally and locally, he says, “it’s fair to say that (independent) hospitals are talking with everyone, feeling that they don’t want to be the last one standing.”

Power Over Price

Hospitals point to the benefits of consolidation. Larger systems have an easier time getting capital for new services or equipment, such as electronic medical records. The e-records, they say, should save money over time through more efficient care and fewer medical errors.

Proponents say that savings can be achieved by what the legislation calls “accountable care organizations” or ACOs.

Rules governing ACOs are still being developed, but it is envisioned that they would include doctors, hospitals and other providers, who would be paid by Medicare to cover all enrollees in a given service area. If the ACO meets quality and cost targets, its executives and doctors would share the expected savings and possibly receive bonuses.

Art by David Plunkert

The ACO concept expands on models that already exist through doctor groups or managed care health plans. One well-known example is the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, which provides care and offers insurance, employs doctors and runs hospitals.

For patients, an ACO could mean swifter referrals from primary doctors to specialists when needed, with less time spent tracking down test results. Those with chronic illnesses, such as asthma or heart disease, would be closely tracked, and those who are hospitalized would suffer fewer readmissions for preventable problems.

Hopkins and others see expansions as a way to position themselves to qualify as an ACO.

There’s no question that the law is driving doctors and hospitals to talk about consolidating, says Brenda Bruns, with insurer Group Health Cooperative, in the Seattle market. With two dominant hospital systems and a number of independent hospitals, it is similar to ones around the nation’s capital where rival facilities are expanding into the suburbs and consolidating into systems.

“The biggest issue is who will be able to partner with whom,” Bruns says. “It’s been ongoing, but the speed has increased because of the whole ACO thing.”

Some fear that if regulators aren’t careful, ACOs could also further fuel consolidation among powerful groups of hospitals and doctors that could drive up costs. By studying such alliances in California, researchers writing in the journal Health Affairs concluded that if ACOs are able to exert more market power in negotiations, “private insurers could wind up paying more, even if care is delivered more efficiently.”

Hospitals And Insurers Slug It Out

Consolidation has added to already tense relations between insurers and hospitals, as both jockey for bargaining power. Insurers are under pressure to slow double-digit premium increases – or face increased scrutiny of their rates. For hospitals, the new law not only emphasizes ACOs, it also calls for smaller Medicare rate increases in the future, offsetting some of the financial benefits of having more insured patients.

Insurers are “playing hardball,” says Chrissy Yamada, the head of finance at independent Evergreen Hospital Medical Center outside Seattle. They want rate decreases, she says, and are backing their demands with threats.

“If you don’t accept their rates the first time, they issue a termination notice,” Yamada says. “This happened twice with us this year. That’s never happened before.”

Hospitals are pushing back, and looking for bigger payment increases. “None are in the single digits,” says Andrew Oliveira, senior medical director for Aetna in the Seattle market. “We’re seeing requests for 10 percent to 40 percent.”

In North Carolina, insurer Aetna and hospital system Novant Health settled a contract dispute in late July, but only after a fight in court. Aetna sent letters to patients and doctors saying Novant was demanding a 13.5 percent increase in payments July 1, on top of a 7.7 percent increase negotiated earlier in the year. Novant fired back with a lawsuit it filed against Aetna for defamation and false advertising, also claiming that the insurer was threatening doctors with being kicked out if its network if they continued to have sole privileges at Novant hospitals.

While disputes in the nation’s capital haven’t been as public, “conversations in the District are just as contentious as they are elsewhere,” Thompson says.

Talks in Maryland are different, he says, because the state takes a larger role in rate-setting between insurers and hospitals. Since the early 1970s, a state commission has approved how much hospitals can charge for services, an effort credited with keeping cost-per-admission rates below the national average.

A ‘Domino Effect’

Thompson thinks Hopkins’ move into Sibley and its Suburban Hospital purchase in Bethesda last year could help lower costs – even as Hopkins adds programs such as expanded cancer treatment.

If Hopkins takes over Sibley, the District will be left with two independent facilities – Howard University Hospital and Children’s National Medical Center. All the other hospitals are owned by either Columbia, Md.-based MedStar Health or other systems, according to a report by the consultancy KPMG. In Maryland, the University of Maryland Medical System controls 19 percent of the state’s hospitals, followed by MedStar with 14 percent and Hopkins with 9 percent, but independents still account for 31 percent of the hospitals, KPMG found. All three systems have bought independents in Maryland in the past three years.

Although the University of Maryland Medical System and Hopkins have long been seen as rivals, John Ashworth III, Maryland’s senior vice president of network development, says the two systems’ expansions so far have played out in a complementary fashion, rather than a competitive one.

Legendary Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore is joining a trend; it expects to add Sibley Hospital in Washington D.C. Experts say mergers have led to higher prices and insurance premiums.

He expects continued consolidation, but says that some facilities are likely to remain independent.

“There are clearly places where remaining independent is absolutely viable,” Ashworth says. “How fast that could change over time because of a better understanding of the health reform law is hard to say.”

Nationally, mergers and acquisitions have leveled off since their peak in 2006, KPMG found. But the mid-Atlantic is bucking the trend. Virginia, for example, had 23 independent hospitals in 2005 and now has 10, according to Mark Higdon, a partner at KPMG. Excluding Sibley, the District has gone from four independents in 2004 to two.

Higdon describes the trend as “a domino effect.”

He says the nation’s capital area is “on the way to becoming a very consolidated market.” And he agrees that such consolidation could slow rising costs. While boosting market share – and gaining leverage over insurers – was a main reason hospitals consolidated 10 or 15 years ago, that is not so much the case now, Higdon says.

Payments from the government and private insurers are going to be more restrictive in the future, he says, and hospitals “have to be more efficient ….. which is one of the major benefits of a larger system.”

Thompson, at Hopkins, says the system will be able to negotiate better deals than Sibley could on its own for supplies, for example. It will also find other efficiencies, although he says he does not anticipate job losses.

Would such savings result in reduced rates to insurers?

“It could, it certainly could,” Thompson said.

The head of Seattle’s Evergreen hospital doesn’t think mergers can save money or give hospitals more negotiating clout with insurers.

“For all the costs you jettison for economies of scale,” Bob Malte says, “you get new costs for being a system.”

And while some hospitals consolidate to better their hand when negotiating rates with insurers, Malte says, “that’s the least noble and least appropriate reason to come together if we’re all trying to lower the cost of care.”

Kaiser Health News reporter Christopher Weaver contributed to this report.