Christine Curtis of Sterling says she is a “happy mom” again, crediting her recovery from debilitating depression to an expensive treatment that sends magnetic pulses into the brain.

“I can’t put a price on it,” said Curtis, 36, who said she feels better than she has in a decade after completing 30 days of the procedure, called repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or rTMS.

An increasing number of psychiatrists and hospitals – as well as entrepreneurs opening rTMS centers around the country – are betting that there are millions of people like Curtis, discouraged by depression treatments that have proved unsuccessful and willing to pony up thousands of dollars for the possibility of relief. The treatment, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, is covered by Medicare in five states, but few private insurers pay for it routinely.

While rTMS has ardent supporters, its effectiveness is still debated, and there is little data showing how long the results last. The technique has been shown to work better than a placebo, but the proportion of patients who show complete relief ranges widely, from as few as 10 percent to as many as 57 percent, according to various studies.

The debate has huge implications, not just for many of the 14 million Americans who suffer from major depression every year but also for businesses eyeing a potentially lucrative market and insurers weighing whether to cover it.

About half of those 14 million seek relief through psychotherapy and prescription drug treatment, according to an evaluation by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. But studies show that antidepressants provide complete cessation of symptoms only about a third of the time. Magnetic stimulation is aimed at patients with such “treatment-resistant depression.”

Supporters say rTMS is worth the cost – between $6,000 and $12,000 for the four-to-six week treatment – because it enables people such as Curtis to resume productive lives.

Skeptics question the price tag in light of uncertain benefits.

“The majority of studies that evaluated rTMS failed to find evidence of an enduring treatment effect after the initial response . . . and some . . . failed to find any significant treatment effect,” concluded Health Plan of Nevada, a UnitedHealthcare insurer, which rejected coverage in March.

With the nation’s health-care spending expected to top $2.7 trillion this year, the battle over paying for rTMS demonstrates why it is so difficult to rein in health-care costs. New technology is generally allowed into the market after studies show it is reasonably safe and more effective than placebos. But that’s not the same as showing it works better than current approaches.

Experts differ over whether it’s smart to cover new approaches if they haven’t proven superior. And they can also disagree over the medical research itself: Was a study done well? Were there enough patients enrolled? Did it ask the right questions? Insurers often call for more research, while doctors and patients – many desperate for help – warn against delay. And costs are rarely discussed publicly.

“As a society, someone has to start looking at cost because eventually — if we’re not already there — we can’t [afford] to do everything,” said Teresa Fama, a Vermont rheumatologist and member of a New England advisory panel created specifically to weigh the scientific evidence and value of treatments like TMS.

‘What Did I Have To Lose?’

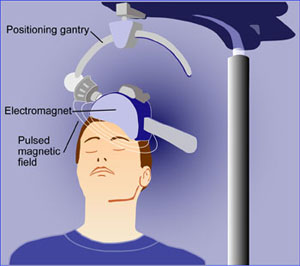

In December, when Curtis first had a magnetic coil placed on her scalp while a $70,000 machine sent pulses into part of her brain, she had already spent a decade trying seven different prescription medications in her battle with depression.

Getting no relief but gaining weight and feeling sluggish and “out of it” because of the drugs’ side effects, she eagerly agreed to the month-long series of five-day-a-week treatments. Most patients have between four and six weeks of near daily sessions.

Curtis’s psychiatrist, Niku Singh, who is also the medical director at TMS NeuroHealth, suggested that she try the procedure. “I was all for it,” said Curtis, whose insurance did not cover the treatment. “It’s a matter of nothing else had worked, so what did I have to lose?”

As the first patient treated at the Tysons Corner facility, which opened in December, Curtis paid only $3,000 because the center needed a test patient to meet the requirements of the device manufacturer. The fee is generally about $10,000, but officials say they work with patients who can’t afford that.

Founders of the center compare rTMS’s potential to that of the now-ubiquitous laser eye clinics; they aim to open a chain of centers nationally that will take walk-ins and accept referrals from physicians. Walk-in patients without a doctor referral would be screened by the center’s medical director to see if they are appropriate candidates.

“We looked at the Lasik model and said, ‘Can we do this with depression? Can we do this with TMS?'” said Bill Leonard, president of the company.

During a treatment, a patient sits in a chair like one in a dentist’s office while an electromagnetic coil is placed against her head. The machine sends four seconds of magnetic pulses into the brain in 26-second intervals, making a woodpecker-like tapping noise. The whole procedure takes about 40 minutes and is monitored by a technician. Patients say it does not hurt. Studies have shown that side effects are few and generally minor, such as headaches and scalp irritations.

Singh said rTMS works by having the pulses stimulate a region of the brain that helps control mood. Research suggests the pulses help depression by activating the release of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. (Singh, who owns two psychiatry practices in the region, says he does not have an investment interest in TMS NeuroHealth.)

Studies Show Range Of Results

The use of rTMS for altering mood or affecting the brain has been studied since at least the early 1990s. After reviewing data from a study of 301 patients, the FDA cleared the device in 2008 for the treatment of major depression in adults who had failed to improve after at least one round of drug therapy.

That study was funded by the device’s manufacturer, Neuronetics, a company based in Malvern, Pa. It found that up to 17 percent of patients treated with the device for six weeks became symptom-free, about twice as many as those treated with a sham rTMS machine.

Subsequent studies have shown a range of results, with about a third of patients reporting complete relief. One 2010 study of 199 “moderately treatment resistant” patients funded by the National Institutes of Medicine found that rTMS was four times as likely to get patients symptom-free as a sham procedure. Patients in that study were treated five times a week for three to five weeks. One key measure – known as the “number needed to treat” – found that one patient became symptom-free for every 12 who were treated.

Supporters such as those at TMS NeuroHealth say they are seeing better results than that among their patients, who can continue taking antidepressants along with their treatment. Curtis, for example, still takes a daily antidepressant four months after completing her treatment, but she has been able to sharply reduce the dosage.

While she noticed no change in her depression at the very start of her rTMS treatment, she said she began feeling better after about two weeks of treatment. “I’m not up and down anymore,” she said.

For patients who don’t respond to prescription drugs and talk therapy, the other major option is electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, in which an electrical current is sent through the brain to deliberately cause a seizure. The procedure, which is more widely used than rTMS, requires two to three treatments a week for three to four weeks and is effective for many patients. But it requires anesthesia and sometimes causes memory loss or confusion.

RTMS does not require anesthesia and its side effects are generally mild. A few small studies have looked at its effects on cognitive function and found either no effect or slight improvement, according to the AHRQ analysis. The costs of ECT — typically about $3,300 for four weeks of thrice-weekly treatments, according to AHRQ data — are covered by most private insurers as well as by Medicare and Medicaid. The cost is higher, however, if a patient must be admitted to the hospital.

Comparable To Drug Therapy

Linda Carpenter, an associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University, who has conducted medical studies using rTMS for depressed patients, says the treatment is effective for some patients, possibly even better than simply trying another medication. But she says questions remain about how long the effects last and how often a patient should return for additional sessions.

“What’s the range of booster treatments people need?” she asks. “Is it once a week, or every couple of years? There’s a huge range in my clinical experience.” Carpenter, a physician, says research has not found any safety issues for patients returning for additional treatments, but cost is a factor.

Most insurers do not routinely cover rTMS because of uncertainty about its long-term effectiveness. Medicare also has mainly rejected coverage, though in January, the administrator of the program’s New England region became the first to approve it, citing the AHRQ report and an assessment by an independent regional advisory board.

That board, called the New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council, voted 10 to 5 last year that studies of the treatment showed it to be as good as or better than usual care for depression. Six of the 10 said it represented a “reasonable” value for its cost; four saw it as a low value. (The same panel voted 9 to 6 that rTMS’s health benefit was equal to that of ECT.) A similar coverage decision proposal is being considered by the Medicare office serving the Washington region.

Even with limited insurance coverage, about 8,000 patients have had the treatment, and the number of treatment centers has doubled to a total of about 400 nationwide since 2010, according to reports by the device’s maker. Centers include some big names, such as Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“The worst thing that can happen is it doesn’t work. We haven’t changed you chemically. We haven’t gone in invasively with surgery,” says Leonard at TMS NeuroHealth.

While that approach may be fine for patients willing and able to spend their own money on treatment, insurers make a different calculation.

“The initial treatment with rTMS is $12,000: That’s a lot of generic Prozac or Effexor,” antidepressants with long track records, says Joel Rubinstein, associate medical director of Harvard Pilgrim HealthCare, a New England insurer that does not cover the treatment. “Managed care has an obligation to a population. You’re shepherding a fixed amount of resources across a large population, and trying to do it according to some sort of evidence-based system.”