Six months after it was controversially hailed by Trump administration officials as a “breakthrough” therapy to fight the worst effects of covid-19, convalescent plasma appears to be on the ropes.

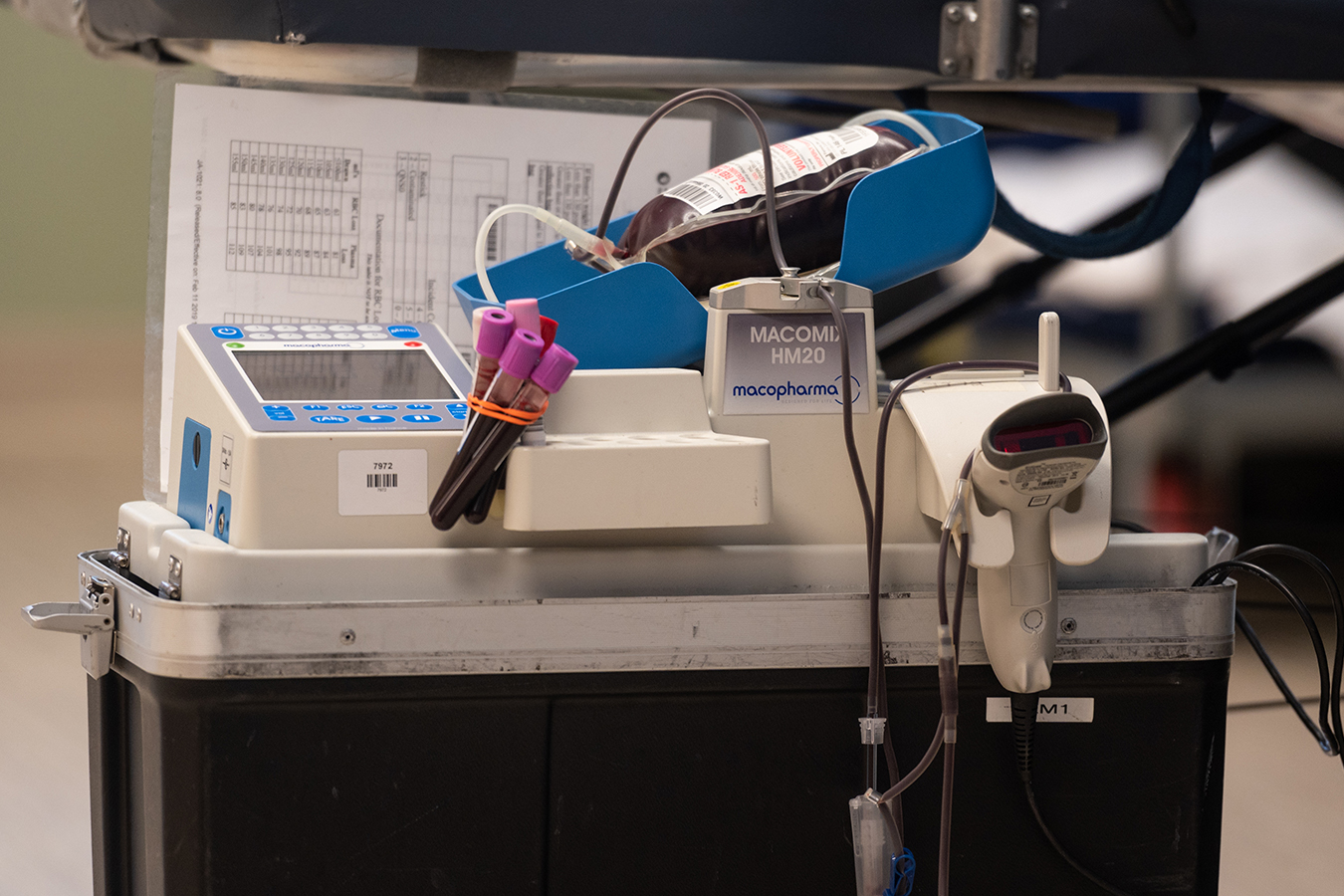

The treatment that infuses blood plasma from recovered covid patients into people newly infected in hopes of boosting their immune response has not lived up to early hype. Some high-profile clinical trials have shown disappointing results. Demand from hospitals for the antibody-rich plasma has plunged. After a year of large-scale national efforts to recruit recovered covid patients as donors and the collection of more than 500,000 units of covid convalescent plasma, known as CCP, some longtime advocates of the therapy say they’re now pessimistic about its future.

“I fear the CCP train has left the station,” said Dr. Michael Busch, director of the Vitalant Research Institute, one of the largest blood-center based transfusion medicine research programs in the U.S. “We created all this enthusiasm, and then these studies came out and they say this stuff didn’t work in the first place.”

But that sentiment is by no means universal. Other respected proponents say we are watching the science progress in real time, and it’s simply too soon to count out convalescent plasma. They note that larger studies employing more calibrated doses of convalescent plasma and more targeted groups of patients, during a set window in their illness, have met the standards for moving forward and may show promise.

“It’s just been a really interesting story to see it unfold,” said Dr. Julie Katz Karp, director of transfusion medicine at Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals in Philadelphia. “People are doing a good job of reading the literature, but one week the answer is ‘yes,’ the next week, ‘maybe not.’”

Convalescent plasma was thrust into the national conversation last August, when the Food and Drug Administration, under political pressure, made the decision to authorize the treatment for emergency use despite objections from federal government scientists cautioning that the therapy was unproven. In the months since, tens of thousands of Americans have been infused with plasma.

Enthusiasm faded in recent weeks following two serious setbacks: A large federal clinical trial, dubbed C3PO, testing the use of convalescent plasma in high-risk patients who came to an emergency room with mild to moderate covid symptoms was halted late last month after researchers concluded that, while the infusions caused no harm, they were unlikely to benefit patients. That same week, a pooled analysis of 10 convalescent plasma studies, published in JAMA, found no clear benefit.

In January, the FDA scaled back the emergency authorization of convalescent plasma, limiting its use to hospitalized covid patients early in the course of the disease and those with medical conditions that impair immune function. The agency also said that only plasma with high concentrations of virus-fighting antibodies could be used after May 31.

At the same time, the covid surge that engulfed the U.S. through much of the winter eased, sending demand for convalescent plasma plummeting. Hospital infusions fell from a high of about 30,000 units a week at the start of the year to about 7,000 per week in early March.

Further complicating matters, federal contracts worth $646 million that paid U.S. blood centers to collect covid convalescent plasma are about to expire, prompting centers nationwide to reconsider whether the complicated process of collecting the plasma is still worth the work. Given the added complexity, blood centers have been reimbursed $600 to $800 a unit for the covid product, compared with the $100 price for a regular unit of fresh, frozen plasma.

“We’re not getting orders,” said Dr. Louis Katz, chief medical officer at the Mississippi Valley Regional Blood Center in Davenport, Iowa. “I don’t want to collect a product that is not going to get used and will cost me more money.”

Officials with the American Red Cross have paused direct collection of convalescent plasma, citing changes required by the FDA’s revised emergency use authorization and an “evolving” market. People previously infected with covid may still donate whole blood, and those units that test positive for high levels of antibodies could be used as CCP.

Even as they acknowledge the setbacks, plasma proponents say declaring its death just a few months into the research would be a foolish overreach. The idea of using plasma from recovered patients to treat the newly ill is a century-old concept that has been employed on an experimental basis during a host of plagues, including the devastating 1918 flu, the 1930s measles outbreak and, more recently, Ebola.

Rather than abandon efforts, scientists need to refine the way convalescent plasma is used and temper their expectations, said Dr. Michael Joyner, principal investigator of the Mayo Clinic-led program that supplied convalescent plasma for more than 100,000 U.S. patients last year.

“This is an unstandardized dose of an unstandardized product being given to all comer patients for a disease with variable progression,” Joyner said in an email. “So it is unrealistic to expect cookie-cutter results like you get for statin/heart attack trials.”

Joyner and others pointed to research that continues to show promise. In mid-February, scientists in Argentina reported that giving convalescent plasma with very high concentrations of antibodies within three days of onset of mild covid symptoms helped slow the progression of disease in older patients. In mid-March, researchers in the U.S. and Brazil reported in a study that has not yet been peer-reviewed that plasma therapy didn’t improve symptoms during hospitalization for patients with severe cases of covid. But it was associated with a 50% reduction in death after 28 days that “may warrant further evaluation,” the authors wrote.

Oversight committees this month gave the nod to two federally funded clinical trials of convalescent plasma to continue enrolling hundreds of patients. One, led by researchers at Johns Hopkins University, is testing convalescent plasma in people who were infected and developed symptoms of covid but were not hospitalized. The other, led by scientists at Vanderbilt University, is testing high-potency plasma in hospitalized patients.

There’s no question “antibodies work against the virus,” said Dr. David Sullivan, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins University and a principal investigator for the institution’s plasma trials.

“It’s all dose and time,” Sullivan said, adding that giving convalescent plasma with high concentrations of antibodies within the first few days of infection is crucial.

The most promising use of convalescent plasma might come from “super donors,” people who were infected with covid and then vaccinated, said Dr. Michael Knudson, co-medical director of the DeGowin Blood Center at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine.

Knudson said his early research shows plasma from recovered then vaccinated people can provide five to 20 times more neutralizing antibody than the plasma from those who have not been vaccinated. “This would be almost a completely different product compared to what is used to date,” he wrote in a presentation to colleagues.

Joyner and others believe “boosted” plasma could be used as a potent antiviral treatment early in infection, similar to how monoclonal antibodies — laboratory-made proteins that act like human antibodies in the immune system — are used. It could be a cheaper option for low-resource countries unable to afford the monoclonal treatments at more than $1,200 per dose.

Even the National Institutes of Health scientists conducting the halted C3PO trial, Dr. Simone Glynn and Dr. Nahed El Kasser, agreed that more data about the usefulness of convalescent plasma is needed. “The answer is no, it is not the final word,” they said in an emailed statement.

But overcoming skepticism about the use of any type of convalescent plasma, let alone “super” plasma, won’t be easy, given the roller coaster of recent results. And broad use of convalescent plasma will depend on continued funding. If the federal contracts with blood collectors are not renewed, covid convalescent plasma likely will be paid for by hospitals or private insurers, depending on where patients receive the treatment.

In the meantime, the federal government, along with academic centers and private donors, has continued to fund the Hopkins and Vanderbilt trials. And the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority has allocated at least $27 million to for-profit companies that collect covid convalescent plasma from paid donors to create hyperimmune globulin, a purified and concentrated form of plasma that may halt disease. Results from late-stage clinical trials of that therapy are expected later this spring.

“I think that it would be a mistake to stop now,” said Dr. Claudia Cohn, chief medical officer of the AABB, an international nonprofit focused on transfusion medicine and cellular therapies. “We have some evidence that it works and evidence that we can produce high-titer plasma. Let’s see what we can do to keep people out of the hospital.”