Neil Dukas knew little about health insurance because he had always been healthy. When he and his wife bought a high-deductible policy in 2008, he didn’t know the difference between a deductible and an out-of-pocket limit. He simply assumed that when he needed care, the insurer would cover it.

But when he injured his knee in July 2008, Dukas, 50, a professional writer in Larkspur, Calif., discovered how difficult it can be to understand and use insurance benefits and get clear, reliable information from an insurer. He also learned how much time and effort it can take to sort through the paperwork.

A key test was held up because of communications difficulties, delaying treatment. Months later, Dukas is still trying to resolve issues with his insurer, Anthem Blue Cross.

Many Americans encounter similar problems. Insurance industry critics say some insurers intentionally make their policies and procedures confusing, and some policy experts believe Congress should require standardized plan information as part of any overhaul of the health system.

The Senate health committee bill would require insurers to meet new standards for honesty and transparency in marketing materials, forms and benefits information provided to plan members. The amendment, added by Sen. Christopher Dodd, D-Conn., would encourage states to establish new consumer assistance offices, and fine insurers that fail to communicate with consumers in plain English.

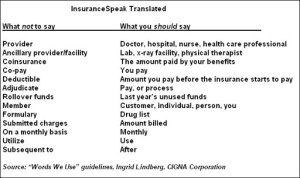

Increasingly, however, health plans are recognizing the problem and making better communications a priority. Some, like CIGNA, are eliminating industry jargon from all oral and written communications with members. A few have developed websites that allow members to estimate their costs ahead of time for care.

Dukas’ story illustrates the range of frustrating problems that can arise in the absence of such efforts.

Baffling statements

His first experience with Anthem occurred when his doctor told him to get the insurer’s authorization for an MRI needed to diagnose his knee injury. Dukas says an Anthem representative told him on the phone that pre-authorization wasn’t needed because the test already had been “reviewed at point of claim” – jargon Dukas didn’t understand.

For four days, suffering severe pain, Dukas went back and forth on the phone between Anthem and his doctor, who insisted on getting pre-authorization to ensure reimbursement for the MRI. He finally paid the doctor the full cost of the MRI, $1,118, putting it on a credit card. The test showed a torn ligament, for which Dukas underwent surgery.

Over the following months, Dukas said he kept calling and writing Anthem about reimbursement for the MRI. And he was baffled by the dozens of pages of benefits statements that Anthem sent him for the thousands of dollars of care he received, much of which would come out of his pocket because of his high deductible. He says it took him “an unbelievable number of phone calls” to match those statements with the doctors’ bills.

“If you get lucky, when you call you get someone attentive and concerned,” he said of his experience with Anthem. “But more often than not it’s someone who has a script, and you have to keep repeating yourself.”

An Anthem spokeswoman declined to comment on Dukas’ case. But she said that miscommunications or delays “occasionally” occur, and that Anthem apologizes for any inconvenience to members.

Insurance experts say even they often have trouble figuring out how to select a health plan, use the benefits, choose a doctor, calculate out-of-pocket costs, resolve disputes and find ways to save money. “I have a hard time with this stuff,” said Janet Ohene-Frempong, a Philadelphia consultant who works with health plans on their consumer communications. “It’s daunting at best.”

Wendell Potter, a former health insurance communications executive, told a Senate committee in June, “There are many ways insurers keep their customers in the dark and purposely mislead them.” Insurers, he said, “make it nearly impossible to understand – or even to obtain – information [consumers] need.”

Making matters worse, large numbers of consumers lack sophisticated reading and number skills. Add to that the growing population of immigrants with limited English language ability, and you have a “perfect storm” for healthcare, said Dr. Ruth Parker, a medical professor at Emory University.

A 2008 survey by eHealth Inc. found that 77 percent of Americans don’t comprehend health insurance terms. “One of the mistakes plans make is assuming people understand all the terms and language,” said Judith Hibbard, a health policy professor at the University of Oregon who has extensively studied healthcare communications. “They don’t, and many people aren’t interested in learning them.”

Regence, a Blue Cross and Blue Shield plan based in Portland, Ore., also discovered last year that many of its members couldn’t calculate a basic medical bill taking into account the deductible, coinsurance, co-pay, maximum out-of-pocket and whether the doctor was in or out of network.

Standard benefits

Dr. Kenneth Thorpe, an Emory University health policy professor who is advising congressional Democrats on health reform, says legislation should require standardized plan information and establish a limited number of standard benefit packages so people are able to make better-informed choices.

The major reform bills would establish health insurance exchanges allowing Americans to select from a menu of plans. The goal, Thorpe said, is “having more standardized product offerings and making it easier to compare across plans, apples to apples.”

Walton Francis, the main author for more than 30 years of Consumers’ Checkbook’s Guide to Health Plans for Federal Employees & Annuitants, published by the nonprofit Center for the Study of Services, says standardized information is key.

Consumers need it, he says, because plans often explain benefits in different and confusing ways. For example, some factor in the deductible and others exclude it in presenting their out-of-pocket limit.

“We have to go into every brochure and look at every footnote to standardize the information,” Francis said. “Even I, a real insurance expert, find it difficult to sort out.”

America’s Health Insurance Plans, the industry trade group, says it would have to look at the details of any proposals for an insurance exchange or standardized information. “We could do a better job of providing information to consumers, but burdensome regulations could stifle innovation and make healthcare coverage unaffordable,” said spokesman Robert Zirkelbach.

Dukas remains angry about the amount of time and effort it took him to deal with the health insurance issues related to his knee treatment.

In March, eight months after the injury, Anthem finally approved his MRI. But Dukas says he is still waiting to be paid back by the insurer. And he’s still calling his insurer and doctors about the confusing benefits and billing statements, in which he’s found errors.

Anthem, for its part, says the medical director and the head of grievances and appeals have been notified about Dukas’ case, and the plan is working to make sure its communications with Dukas are “clear and accurate moving forward.”