Indiana on Friday became the second state to win federal approval to add a work requirement for adult Medicaid recipients who gained coverage under the Affordable Care Act, but a less debated “lockout” provision in its new plan could lead to tens of thousands of enrollees losing coverage.

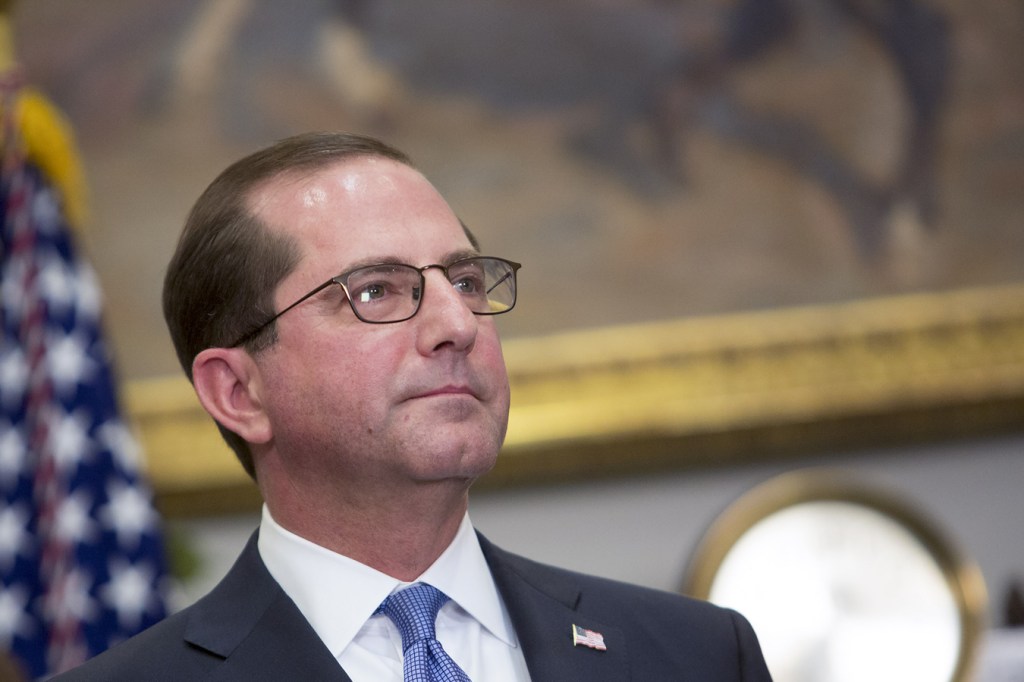

The federal approval was announced by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in Indianapolis.

Medicaid participants who fail to submit in a timely manner their paperwork showing they still qualify for the program will be blocked from enrollment for three months, according to the updated rules.

Since November 2015, more than 91,000 enrollees in Indiana were kicked off Medicaid for failing to complete the eligibility redetermination process, according to state records. The process requires applicants to show proof of income and family size, among other things, to see if they still qualify for the coverage. Until now, these enrollees could simply re-apply anytime. Although many of those people likely were no longer eligible, state officials estimate about half of those who failed to comply with its re-enrollment rules were still qualified.

Indiana’s Medicaid expansion began in February 2015, providing coverage to 240,000 people who were previously uninsured, helping drop the state’s uninsured rate from 14 percent in 2013 to 8 percent last year. The HHS approval extends the program, which was expiring this month, through 2020.

The new lockout builds on one already in place in the state for people who failed to pay monthly premiums and had annual incomes above the federal poverty level, or about $12,200 for an individual. They are barred for six months from coverage. During the first two years of the experiment, about 10,000 Indiana Medicaid enrollees were subject to the lockout for failing to pay the premium for two months in a row, according to state data.

In addition, more than 25,000 enrollees were dropped from the program after they failed to make the payments, although half of them found another source of coverage — usually through their jobs.

Another 46,000 were blocked from coverage because they failed to make the initial payment.

“The ‘lockout” is one of the worst policies to hit Medicaid in a long time,” said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. “Forcing people to remain uninsured for months because they missed a paperwork deadline or missed a premium payment is too high a price to pay. From a health policy perspective it makes no sense because during that period, chronic health conditions such as hypertension or diabetes are just likely to worsen.”

Indiana’s Medicaid expansion is being closely watched in part because it was spearheaded by then-Gov. Mike Pence, who is now vice president, and his top health consultant, Seema Verma, who now heads the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The expansion, known as Healthy Indiana, enabled non-disabled adults access to Medicaid. It has elicited criticism from patient advocates for complex and onerous rules that require these poor adults to make payments ranging from $1 to $27 per month into health savings accounts or risk losing their vision and dental benefits or even all their coverage, depending on their income level.

Indiana Medicaid officials said they added the newest lockout provision in an effort to prompt enrollees to get their paperwork submitted in time. The state initially requested a six-month lockout.

“Enforcement may encourage better compliance,” the state officials wrote in their waiver application to CMS in July.

The new rule will lead to a 1 percent cut in Medicaid enrollment in the first year, state officials said. It will also lead to a $15 million reduction in Medicaid costs in 2018 and about $32 million in savings in 2019, the state estimated.

The number of Medicaid enrollees losing coverage for failing to comply with redetermining their eligibility has varied dramatically each quarter from a peak of 19,197 from February 2016 to April 2017 to 1,165 from November 2015 to January 2016, state reports show. In the latest state report, 12,470 enrollees lost coverage from August to October 2017.

The Kentucky Medicaid waiver approved by the Trump administration in January included a similar lockout provision for both failing to pay the monthly premiums or providing paperwork on time. Penalties there are six months for both measures. But the provision was overshadowed because of the attention to the first federal approval for a Medicaid work requirement.

Like Kentucky, Indiana’s Medicaid waiver’s work requirements, which mandate adult enrollees to work an average of 20 hours a month, go into effect in 2019. But Indiana’s waiver is more lenient. It exempts people age 60 and over and its work-hour requirements are gradually phased in over 18 months. For example, enrollees need to work only five hours per week until their 10th month on the program.

Most Medicaid adult enrollees do work or go to school or are too sick to work, studies show.

Indiana also has a long list of exemptions and alternatives to employment. This includes attending school or job training, volunteering or caring for a dependent child or disabled parent. Nurses, doctors and physician assistants can give enrollees an exemption due to illness or injury.

Three patient advocacy groups have filed suit in federal court seeking to block the work requirements.

Robin Rudowitz, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said it’s difficult to gauge whether work requirements or renewal lockouts will have more of an impact on coverage. She noted both provisions apply to most demonstration beneficiaries. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation).

“Any documentation requirement could lead to increased complexity in terms of states administering the requirements and individuals complying,” she said, adding that it could result “in potentially eligible people falling off of coverage.”