Every week, KHN reporter Shefali S. Kulkarni selects interesting reading from around the Web.

The New York Times: Keeping Parkinson’s Disease A Secret

When Nancy Mulhearn learned she had Parkinson’s disease seven years ago, she kept the diagnosis mostly to herself, hiding it from friends, colleagues — even, at first, her mother, sister and teenage children. After seven months, she decided she had to tell her family, and they settled into an unspoken agreement not to talk about the disease. … “I didn’t want anybody to feel sorry for me,” she said. “To have people look at you and start crying — that’s not what anyone wants.” In that, Ms. Mulhearn is hardly alone. Doctors and researchers say it’s not uncommon for people with Parkinson’s to conceal their diagnoses, often for years. But the secrecy is not just stressful to maintain; experts fear that it also may be slowing down the research needed to find new treatments (Katie Yandell, 7/9).

Slate: Dr. Drew Cashes In

If you’ve ever seen Dr. Drew Pinsky on TV, you’ve seen the look: lips pursed, eyes narrowed, head slightly tilted to stage right. It’s an expression that seems practiced in front of a mirror, designed to dispense to his troubled patients precisely the right dosage of compassion tinged with disapproval — but, instead, it makes him look like his mind is somewhere else, off golfing or figuring out where his next paycheck is going to come from. Thanks to the Justice Department, we now know of a Dr. Drew payday large enough to trigger a reverie or two. As part of its monstrous $3 billion settlement with the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the DOJ unsealed documents showing that the dear doctor had taken in at least $275,000 for “services for Wellbutrin.” … According to the government’s complaint, Dr. Drew was hired to “deliver messages about [Wellbutrin SR] in settings where it did not appear that Dr. Pinsky was speaking for GSK.” After Pinsky suggested that Wellbutrin might be responsible for increasing a woman’s orgasm rate — to as many as 60 orgasms in a good night — an internal GSK memo noted approvingly that Dr. Drew had “communicated key campaign messages” about Wellbutrin to the public (Charles Seife, 7/9).

Earlier from KHN: Doc Payments Show Underbelly Of Pill Marketing

The Economist: A Sweet Idea

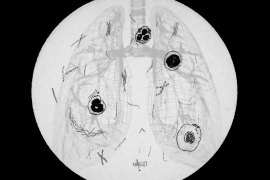

Like any other electrical device, a pacemaker needs a power source. Since the first permanent pacemaker was installed in 1958, manufacturers of implantable medical devices (IMDs) have tinkered with many different ways of supplying electricity to their products. A variety of chemical batteries have been tried, as well as inductive recharging schemes and even plutonium power cells that convert the heat from radioactive decay into electricity. … Today, non-rechargeable lithium-based batteries are common. Used in many cardiological and neurological implants, they provide between seven and ten years of life. … But that has not dissuaded researchers from continuing to seek perfection, in the form of a compact, perpetual energy source which does not require external recharging. Now, several researchers are closing in on just such a solution using glucose, a type of sugar that is the main energy source for all cells in the body (6/30).

The Journal Of The American Medical Association: Learning To Talk

The more doctor-speak becomes second nature to us, the more it can distance us from our patients. It is easy to lose sight of the possibility that even the most basic medical words may be jibberish to our patients. … I recently caught myself launching into a monologue from the door in the emergency department about precautions to take and what to expect after a concussion to a 22-year-old patient. I paused, examined his frightened face, and then asked if he knew what a concussion was — he hesitated, then shyly shook his head no. I sat down by his bed, started over, and walked him through it. I felt like I had made a connection (Dr. Alison Landrey, 7/11).