Dr. Adil Haider, a trauma surgeon and assistant professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, thought trauma would be the one medical area free from racial disparities — emergency rooms don’t check insurance, and they are required to treat anyone who comes through their doors.

“With trauma, you call and the ambulance comes. We think we treat everyone the same when they come into the Emergency Department,” he said. But he and his research colleagues found Hispanic and black trauma patients faced a higher risk of death compared to whites—especially if they are served in hospitals with a high percentage of minority patients.

“Patients treated at hospitals with higher proportions of minority trauma patients have increased odds of dying. … Differences in outcomes between trauma hospitals may partly explain racial disparities,” the researchers wrote in the study, which was published this month in the Archives of Surgery. The study also found that “minority patients, whether black or Hispanic, did not have worse outcomes at predominantly majority hospitals. Similarly, there was no difference in odds of mortality for whites, blacks, or Hispanics at predominantly minority hospitals.”

But the issue of mortality at trauma facilities is more than skin-deep. By studying data from the National Trauma Data Bank from 2007 to 2008, “we showed that your race and your insurance status both predicted mortality.” Haider says. In an earlier study, the researchers found that overall a black trauma patient compared to a white trauma patient had a 20 percent higher risk of death, he said. Similarly, a white patient without insurance had approximately 50 percent greater chance of mortality compared to a white insured patient. “If you were uninsured and you were a minority, there was a cumulative effect, and it was even worse than that,” Haider said.

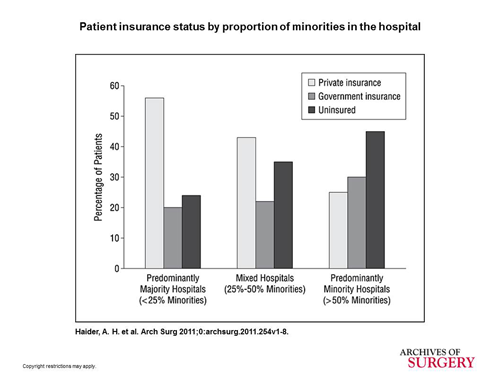

For this study, the researchers sorted hospitals into three categories using data from the National Trauma Data Bank. Majority hospitals served mostly white patients; minority hospitals served predominantly black and Hispanic patients, and mixed hospitals served an even proportion of white, Hispanic and black patients. Minority hospitals had a large percentage of patients lacking insurance, while majority hospitals appeared to have most of their patients insured.

“Insurance is really more than the ability to pay a bill, it’s also an indicator of social-economic status. Not a true, perfect exact indicator, but it gives you a sense of the person’s social-economic status,” Haider says. “The hospitals that are treating the bulk of minority patients, they are doing this with a much smaller number of insured patients. So obviously that would lead to some struggle and some difficulty.” The study cites that this “payor mix disparity” can affect the care a critically injured patient receives.

“I don’t want anyone to get the conclusion that these minority hospitals are doing a bad job — if you look at the insurance profiles, you’ll see that they are doing a very difficult job. It’s not a level playing field. What this paper basically says is that we need to really strengthen those hospitals that are taking care of these minority patients. We don’t need to look at them as the lower performing hospitals, we need to look at them as the lower resourced hospitals. We need to do something to strengthen them so their outcomes could be equal to those hospitals that have all those insured patients.”