Republican leaders have a lengthy list of talking points about the shortcomings of the health law. Shortly before his inauguration last month, President Donald Trump said that it “is a complete and total disaster. It’s imploding as we sit.” And they can point to a host of issues, including premium increases averaging more than 20 percent this year, a drop in the number of insurers competing on the Affordable Care Act marketplaces and rising consumer discontent with high deductibles and limited doctor networks.

Yet a careful analysis of some of the GOP’s talking points show a much more nuanced situation and suggest that the political fights over the law may have contributed to some of its problems. Here is an annotated guide to four of the most common talking points Republicans have been using.

1. The individual health insurance market is collapsing.

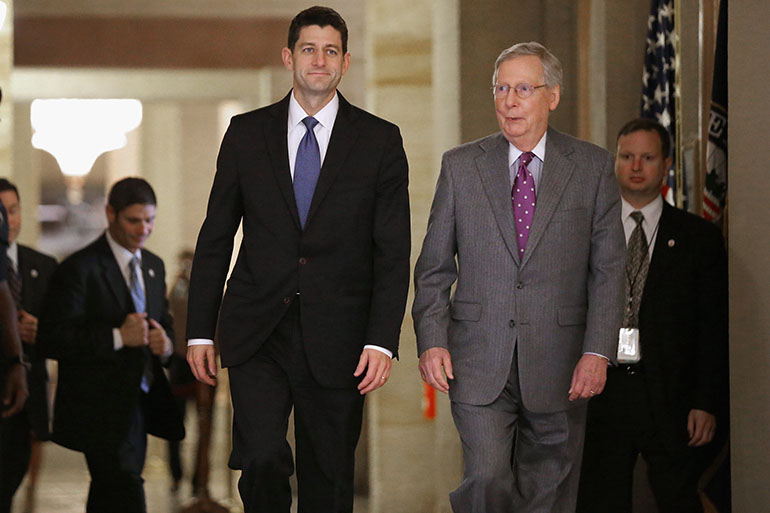

— House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), on Meet the Press, Feb. 5, “the law is literally in the middle of a collapse.”

— Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), on the Senate floor Jan. 9: “Obamacare continues to unravel at every level, leaving Americans to pick up the pieces.”

Republicans are right that the individual market that the Affordable Care Act sought to overhaul is having challenges right now. Many insurance companies left the market at the end of 2016 after losing money, which reduced choices for individuals, and five states have only a single insurer providing coverage in 2017.

But even with these challenges, the health law’s marketplaces, also called exchanges, are providing coverage to more than 10 million Americans. Some analysts say they are far from collapse.

“I have never believed the individual market was in a true death spiral,” said Joe Antos of the conservative American Enterprise Institute. A death spiral is when so many healthy people leave a market that only sick people are left and insurers cannot spread costs.

Insurance markets also vary a lot by state, said John Ayanian, head of the University of Michigan’s Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation. “There are a fair number of states where the exchanges are working fairly well, costs are not rising too quickly, and people have a number of choices of health plans,” he said. “There are other states where they have just one choice and prices are going up.”

At the same time, legislation written by Republicans has led to some of the trouble in exchanges. Most directly, Congress limited federal payouts to insurers who encountered higher-than-expected costs in the exchanges. Republicans called the payments “insurance company bailouts,” even though similar federal measures have been used in other markets, such as the Medicare drug plans implemented more than a decade ago.

Still, the result was that the Department of Health and Human Services was able to provide insurers with only 13 percent of the money they were promised under the law in 2015. That shortfall led directly to the implosion of most of the nonprofit co-op health plans, and some private insurers referenced the shortfalls when they pulled out of the marketplaces this year. Yet when House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Greg Walden, R-Ore., noted at a Feb. 2 hearing that “only five out of the original 23 insurance co-ops remain. … They tried it, it didn’t work,” he did not mention the loss of the federal payments to cover early losses.

2. Out-of-pocket spending is too high.

— Speaker Ryan, at CNN Town Hall Jan 12: “Deductibles are so high it doesn’t even feel like you’ve got insurance anymore.”

— Senate Majority Leader McConnell (in a CNN op-ed): “It’s raising health care costs by previously unimaginable levels, and it’s hurting the very people it was intended to help.”

Out-of-pocket spending is one of voters’ top concerns when it comes to health care. The January 2017 monthly tracking poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation found 67 percent of those polled said their top health priority is “lowering the amount individuals pay for health care,” followed closely by “lowering the cost of prescription drugs” at 61 percent. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent project of the foundation.)

High deductibles — often in the thousands of dollars — have become part of that problem.

People who are most angry about the Affordable Care Act, said Chris Jennings, a health official in the Clinton and Obama administrations, “want deductibles lower and more benefits.”

But Republicans’ most popular proposals for replacing current individual insurance plans — cutting back on required benefits and giving more people access to tax-preferred health savings accounts — would likely increase out-of-pocket spending for those who use health services (although it would be less expensive for people who are healthy all year long).

Letting people buy more bare-bones policies “means insurance doesn’t kick in until people have very significant medical bills,” said Ayanian.

Former Obama administration health official Sherry Glied, on a panel at the National Health Policy Conference in January, asked if having a $10,000 or $20,000 deductible (as some proposals would allow) with perhaps $1,000 in a health savings account “is better than having no coverage at all? Lots of people would go bankrupt at $20,000,” particularly if they don’t have the resources to fund the HSA with their own savings.

3. Medicaid patients can’t find doctors to treat them.

— Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.), on the Senate floor Jan. 9: “It is the illusion of coverage without the power of access.”

— Speaker Ryan, from CNN Town Hall Jan. 12: “… so our concern is, that people on Medicaid can’t get a doctor and if you can’t get a doctor, what good is your coverage?”

Studies do suggest that low pay (each state sets its own rates) does decrease physician participation in Medicaid, and finding specialty care can be difficult in some parts of the country. But overall the academic literature shows that Medicaid patients have a far easier time, and are far more likely to obtain health care services than people with no insurance.

Benjamin Sommers of the Harvard School of Public Health, who has studied the issue, said the idea that patients with Medicaid can’t get care comes from looking overall at how many doctors and other providers accept the program’s generally lower payments and higher administrative burdens. “But that’s not the best way to study this. The best question … is when you talk to the people with coverage and ask them if they can get the care they need.”

And he said “study after study” shows that “when people get Medicaid, their access to care improves dramatically,” including greater use of primary care, preventive screening, and care of chronic conditions. “Even with some potential limitations of provider participation, patients are much better off once they get that [Medicaid] coverage,” he said.

4. The ACA has reduced jobs.

— Tom Price, the secretary of Health and Human Services, during a confirmation hearing before the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee Jan. 18: “The ACA has decreased the workforce by the equivalent of 2 million FTE’s (full time employees).”

— Senate HELP Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), on the Senate floor Jan. 9: “Across the country … employers have cut jobs to afford Obamacare costs.”

Much of this talking point stems from a report by the Congressional Budget Office in 2014 that projected the nation’s workforce would drop by about 2 million jobs due to the health law, as well as anecdotal reports about employers cutting workers hours to avoid triggering the law’s requirement that they offer health insurance.

But a careful reading of the CBO report notes that the decline they estimate would be due less to employers cutting back, and more to older workers voluntarily opting to work fewer hours — perhaps because of fears of losing their premium subsidies or their Medicaid eligibility — or retiring because they no longer had to work in order to get health insurance.

It is true that some employers cut worker hours below the 30-hour threshold to avoid the employer coverage requirement.

However, the strengthening economy, including in the health care sector, has shrunk the part-time workforce and expanded full-time employment well beyond the numbers reduced by the Affordable Care Act, according to most analysts. In fact, so many jobs have been created in the industry since the ACA became law that it is becoming a problem itself, because having such a vast chunk of the economy devoted to health care makes it harder to reduce health spending.