An Alaska man developed gangrenous toes. A Philadelphia woman froze to death on the street. An Illinois woman died emaciated, covered in excrement.

These patients suffered as their government-paid caretakers neglected them, collecting paychecks under a Medicaid program that gives elderly and disabled people non-medical assistance at home. In some cases, the caretakers convicted of neglect were the victims’ own family members.

The Personal Care Services program, which exceeded $14.5 billion in fiscal year 2014, is rife with financial scams, some of which threaten patient safety, according to a recent report from the Office of lnspector General at the Department of Health and Human Services.

The OIG has investigated over 200 cases of fraud and abuse since 2012 in the program, which is paid for by the federal government and administered by each state. These caretakers, often untrained and largely unregulated, are paid an average of $10 per hour to help vulnerable people with daily tasks like bathing, cleaning and cooking.

The report exposes vulnerabilities in a system that more people will rely on as baby boomers age. Demand for personal care assistants is projected to grow by 26 percent over the next 10 years — an increase of roughly half a million workers — according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

“This type of industry is ripe for fraud,” warned Lynne Keilman-Cruz, a program manager at Alaska’s Department of Health and Social Services who has investigated widespread fraud. The risks increase because the care takes place out of view in people’s homes, and because neglected patients may not advocate for their own care.

The OIG report describes a range of rip-offs, some of which involve caretakers caught up in the nation’s opioid epidemic. In one Illinois case, a woman whose nursing license had been suspended for allegedly stealing drugs at work signed up as a caretaker. She billed Medicaid for $34,000 in caretaking services she didn’t provide — including charges made while she was on a Caribbean vacation. In Vermont, a caretaker on probation for drug possession split her paychecks with the patient’s wife — in exchange for stealing the patient’s prescription painkillers, while he lay in visible discomfort.

In other cases, Medicaid beneficiaries colluded in hoaxes, faking disability so they could hire unneeded help.

In the worst cases, patients got hurt, sometimes fatally.

In Philadelphia, Christina Sankey, a 37-year-old woman with severe autism, froze to death on the street after her caretaker, Hassanatu Wulu, lost her in a crowded Macy’s five miles away. Wulu, 32, pleaded guilty to neglect.

In some cases, elderly patients were neglected by their own children, who signed up for caretaker payments. In Idaho, a woman was hospitalized for severe dehydration and malnourishment after her son and caretaker, Paul J. Draine, neglected her. Investigators found the home they shared littered with drug paraphernalia. Draine pleaded guilty to fraud and abuse or neglect, and was sentenced to a sober home.

In Illinois, a woman was found incoherent and covered in feces after her daughter and caretaker, Jessica Teets, of Granite City, failed to show up for over a week. The woman, Susan A. Smith, who loved crocheting and quilting, died seven months later at just 46. Teets was convicted of fraud and sentenced to five years’ probation.

Investigators provided no count of how many cases of fraud and abuse involved relatives, but “it’s fairly common for family members to be the attendants, and it’s fairly common for those same family members to be the ones who are abusing, neglecting, or committing fraud,” said David Ceron, an OIG special agent based in Washington, DC. In California, three-quarters of Medicaid-funded personal assistants are relatives, though some states restrict hiring family members.

In California, a Kaiser Health News investigation last year revealed widespread problems, as well as a lack of training and oversight, in the state’s program, which is the largest in the U.S.

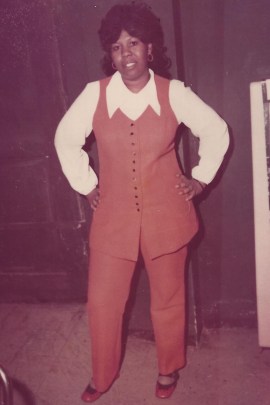

Dorothy Cooper of Cahokia, Illinois, died emaciated and malnourished in 2013; her Medicaid-funded caretaker was convicted of fraud in connection to her death by neglect. (Undated family photo)

In one disturbing Illinois case, a family member found 62-year-old Dorothy Cooper on the floor in her home in Cahokia, Illinois — covered with feces, malnourished, with bone-deep ulcers and open wounds. She was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Lisa Luckett, her alleged caretaker, who was disabled herself, had billed Medicaid for Cooper’s care for more than six years using fraudulent names. Cooper’s death in 2013 was ruled a homicide. Luckett, who had a prior child neglect conviction, pleaded guilty to fraud and was sent to prison for four years.

At the funeral home, Cooper looked “like she was a malnourished animal, just skin and bones,” her niece, Jacqueline Cooper-Cannon, said in an interview. Luckett “neglected my aunt, and it was a horrible death for her.”

The negligence extended beyond the caregiver to the system, which failed to dig into Luckett’s criminal history, notice forged signatures or monitor Cooper’s wellbeing, her niece said. She called on the state to institute mandatory training and background checks.

The inspector general’s office, which has documented years of fraud and neglect in the program, urged federal action. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services requires no standard training — nor background checks — for personal care attendants. Fraud can be hard to track, because many states don’t register caretakers, or even identify the worker in Medicaid claims, the OIG report found.

In the report, the OIG called on CMS to establish national qualifications, including background checks, and ensure every claim identifies the worker and time of service. It also called on CMS to require states to enroll all personal assistants, so they can be tracked by unique numbers.

That’s just what Alaska has done. It began requiring enrollment for personal care assistants in 2011 and now has 8,000 workers assigned unique identifying numbers, used with every claim.

The system helped investigators determine that Good Faith Services, a large home health care company in Alaska, was billing Medicaid for half a million dollars’ worth of caretaker services never performed. Its workers made claims while they were out of the country, or after Medicaid beneficiaries were dead. As part of a criminal prosecution that convicted 50 people, the company dissolved and its owner, Agnes Francisco, pleaded guilty to fraud. She was sentenced in 2015 to three years in prison, and ordered to pay $1.5 million in restitution and fines.

Cooper’s case is representative of the fraud and abuse in Medicaid’s Personal Care Services program. (Undated family photo)

That case couldn’t have been cracked without the state database of workers’ identifying numbers, Keilman-Cruz said. The system enabled the state to see that one caretaker billed over 24 hours of service in a day. Another caretaker purported to be in Anchorage caring for one patient, just two minutes after caring for another patient in a town an hour away, Keilman-Cruz said.

In one case, Keilman-Cruz visited the home of a 63-year-old man with diabetes who had signed up to receive home help. The man told her that no help ever came — though a man would knock on his window and ask him to sign paperwork that he didn’t understand. Without a caretaker to bathe him, dress him and remind him to take medications, the man’s diabetes intensified and he grew gangrene on his toes, Keilman-Cruz said. The window-knocker, who had been falsifying timesheets, was later charged with fraud, as was his wife, who claimed to be the caretaker but never entered the home.

Alaska and Minnesota are among the states that now require caretaker enrollment. If other states followed suit, Keilman-Cruz said, “they would have eyes into all of the scams that we’ve uncovered.”

To detect impropriety, Illinois now requires personal assistants to call in at the beginning and end of each client visit; their phone calls are recorded in an electronic database, according to the Department of Human Services.

Meanwhile, CMS is trying to strengthen the program’s integrity, spokesman Tony Salters said. In February, CMS started training states to monitor “fraud, waste and abuse,” he said. The agency also published a bulletin offering states several options, including creating a registry, where consumers could look up which caretakers meet state qualifications.

But disability groups have pushed back against stricter regulations, arguing they don’t want to limit Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to caretakers. So CMS is treading lightly.

Instead of making background checks mandatory, CMS has granted $50 million to 26 states to set up background check programs.

And instead of requiring mandatory training, CMS has offered states the option of offering basic caretaker training — “without usurping beneficiary decisions on what skills are most appropriate for their homecare workers,” Salters said.

KHN’s coverage of end-of-life and serious illness issues is supported by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.