A 12-year-old boy named Strazh hangs from the monkey bars, staring at the ground. The other kids in the park aren’t interested in him. And he’s not interested in them.

“I just like to play by myself,” he says.

Strazh has autism. Today is a good day. But on most others, Strazh has meltdowns. Something frustrates him and he can’t control his emotions.

“I sometimes end up screaming,” he says. “And I end up yelling and screaming.”

And hitting and banging things, throwing things, adds Strazh’s mom, Natalie Dunnege. As a single parent, she says she bears the brunt of it.

“He told me that I disgusted him,” she says softly. “He tells me he hates me.”

Dunnege puts all her spare money into therapy for Strazh. She says it helps a lot. But Dunnege herself is struggling, feeling depressed and overwhelmed. She decided to look for her own therapist.

“One of the things that I’ve really had to wrap my head around is that I can’t change him. I can only change how I handle the situation,” she explains. “And not that I would want to change who he is. He’s a really good kid, but it’s a lot to handle, especially as a single parent.”

But when she logged onto her insurance website to find a therapist, she realized her copay for a mental health visit was going to be upwards of $75 — more than double her copay for other doctors’ appointments. Under a 2008 federal mental health law, those copays are supposed to be the same.

“There’s no way,” Dunnege says. “It’s out of my budget right now.”

Dunnege lives in a one-bedroom apartment with her son and her father in San Francisco’s Haight district. Grandfather and grandson sleep in twin beds side by side. It’s an awkward walk past those beds to the only bathroom. Dunnege says $75 a week for therapy is impossible.

“My income, I just made lower middle income. Just by the skin of my teeth,” she says. “So I just have to hold off until I’m actually middle class.”

Natalie Dunnege and her son, Strazh, work on an art project at home. (Sheraz Sadiq/KQED)

More than 43 million Americans suffer from depression, anxiety and other mental health conditions, according to the most recent federal data. But more than half the people who felt like they needed help last year, never got it. Even people who had insurance complained of barriers to care. Some said they still couldn’t afford it; some were embarrassed to ask for help. Others just couldn’t get through the red tape.

Recent health laws, the 2008 Mental Health Parity Act and the Affordable Care Act, were supposed to fix this. They require health plans to provide benefits for mental health conditions on par with physical health conditions. Under the law, insurance companies can’t charge higher copays or set up separate deductibles for mental health care compared to other medical or surgical care. They can’t limit hospital stays or require preauthorization for mental health treatment if the same limits are not applied to treatment for physical health conditions.

But advocates say insurance companies are still finding ways to keep people who need care from getting it. Some are still not complying with the law. And some have found subtle, technically legally, ways to limit treatment.

Problems With Mental Health Provider Directories

Natalie Dunnege encountered some of these barriers when she tried again to find a therapist. In the last year, she got a promotion at work and moved into a larger apartment. Her employer switched to a better health plan, too. Now she has Blue Shield coverage, and her copay for mental health appointments is only $20.

“Which I was really excited about,” Dunnege says.

But when she looked for a therapist who took her insurance, she struck out.

“I contacted six or seven,” she says.

Only three called her back.

“One of them, they were completely booked,” she says. “And then the other two just didn’t accept the insurance anymore.”

Zero hits out of seven. Had to be a bad draw, right?

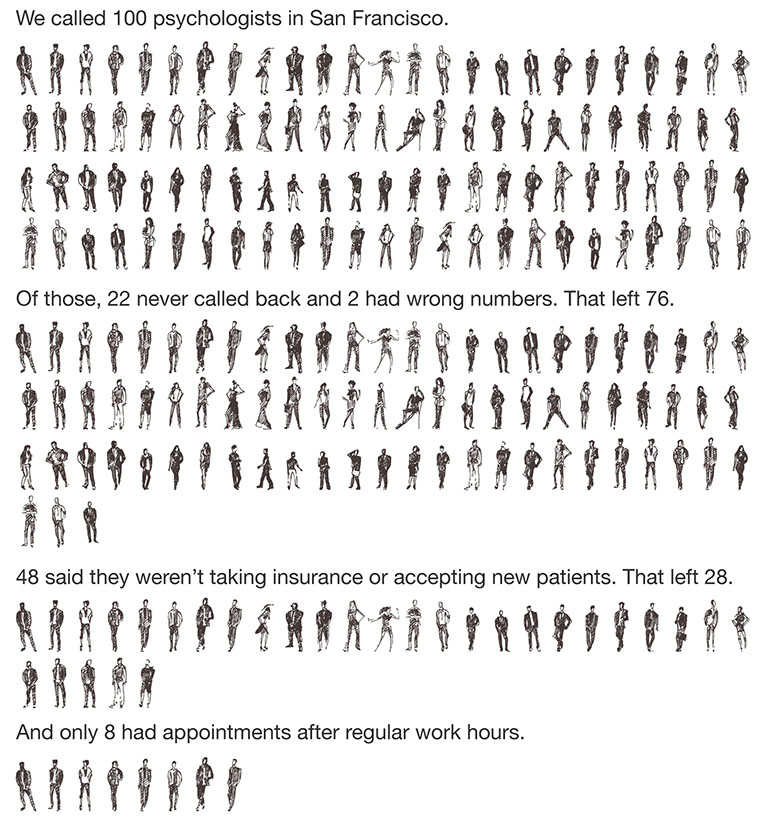

To find out, we decided to conduct our own survey and called all the psychologists — 100 in total — that were listed on the Blue Shield website for Natalie’s plan in San Francisco.

Here’s what happened:

(Lisa Pickoff-White/KQED)

The end result: 28 psychologists actually had appointments. And only eight of them had slots available outside regular work hours. Eight out of 100.

“Sorry, I wish you the best of luck,” was a common refrain in therapists’ voicemail messages.

For Natalie Dunnege, after seven rejections, she gave up looking.

“It’s hard when you’re feeling sad and you feel like you can barely keep things together,” she says. “It just seemed like way too much at the time.”

Mental health advocates say this is exactly what insurance companies are hoping.

“It’s a way to control cost,” says Keith Humphreys, a Stanford psychiatry professor who served as an advisor to Congress when it was developing the 2008 Mental Health Parity Act. He says while insurers are now required to keep an adequate number of clinicians listed in their directories, they still find ways to sidestep the rules.

“You know the law doesn’t say you can’t put people on there who are dead, or you can’t put people on there who are not taking new patients,” he says. “What that translates into, then, is people have to wait longer for care, which then cuts expenditures for the insurer and reduces access.”

California passed a law last year, SB 137, raising the standards for physician directories. Insurers will have to police their lists for providers who are booked or retired. But a lot of questions remain about how the law will be enforced, especially when it comes to mental health providers, who are largely self-employed, solo practitioners.

The insurance industry says it will be a challenge.

“When you have networks as large as ours and you have as many enrollees as we have here in California, you’re not going to be able to just have everything accurate every single second of every single day,” says Charles Bacchi, CEO of the California Association of Health Plans.

He said the industry is working to make it better.

“But we also need to be realistic,” he says. “We don’t run a mental health provider’s office. They do. And how they handle people calling their offices is their job.”

In a statement, Blue Shield said it tries to make it easy for providers to update changes in their contact information and schedule.

“We understand that there are a number of issues that impact a provider’s availability to take new patients, such as administrative limitations and fluctuating numbers of patients based on their individual needs. When those instances arise, the provider is required to notify us so that patients have access to the most up-to-date information about who is available in their area.”

The industry also says it’s facing another challenge: a nationwide shortage of mental health providers, further exacerbated by the millions of people who signed up for insurance under the Affordable Care Act.

In California, there are “around 4 to 5 million more people with coverage, just in the last two years,” Bacchi says. “And that’s creating a strain for everybody, plans and mental health providers.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes KQED, NPR and Kaiser Health News.