A guide helps consumers understand what they can expect in a health insurance policy.

Choosing a health insurance policy should be easier if consumers use the simple chart and other information that state insurance commissioners approved Thursday.

“It will force the insurance companies to reveal information in a consistent way,” says Bonnie Burns, a policy specialist for California Health Advocates, a consumer health advocacy group. “And it should make it easier for people to understand what they’re getting and not getting.”

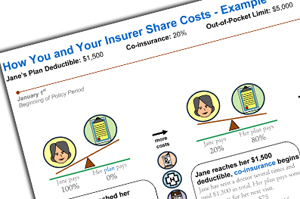

Under a little-known provision of the health overhaul law, insurers will be required to provide their benefits information on a standardized chart using the same plain English terms as other companies to help shoppers understand and compare complicated policies. Congress even listed some of the insurance jargon including terms such as deductible, preferred provider, excluded services and UCR (usual, customary and reasonable) that must be defined in a glossary that will accompany the benefit summary. It directed the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to form a group to develop the materials and specified that the group include state insurance regulators, consumer and patient advocates, insurance companies and health care providers.

The materials, which had been adopted unanimously by the working group, will be sent to the Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Labor. Those departments will issue regulations spelling out how insurance companies and employers must use the materials. The new system must be in place by March 2012.

“Right now I think it’s really hard for buyers today to shop for coverage, compare apples to apples and make smart decisions,” says Mila Kofman, Maine’s superintendent of insurance and a co-chair of the working group.

Only a handful of states require health insurers to distribute information that meets “readability standards,” she says.

It wasn’t easy for the group to decide what information consumers needed when choosing a policy and to translate insurance jargon “so that a normal person understands what it is,” says Kofman. The group’s nearly four dozen members held 25 meetings and conference calls, some as long as six hours.

“It’s a great way to educate consumers about insurance,” says Randy Kammer, a vice president of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Florida and a member of the working group. It tells them what kind of information they need to consider when choosing a policy and “will create incentives for them to look deeper.”

The draft benefits summary and a glossary of definitions were tested on consumers in focus groups in the fall by Consumers Union and the America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry group. Their reactions prompted some refinements.

The law even forbids the dreaded “fine print,” by specifying at least a 12-point type size (larger than typical newsprint). Any exceptions or limitations to coverage must be included along with the out-of-pocket costs that plan members can expect to pay. Examples of the costs for some common medical treatments must also be provided in a separate “coverage facts label” modeled after the nutrition facts label that appears on prepared foods. Kofman says the group has not finished its work on the label.

Kofman does not expect the government to make many changes when it reviews the consumer materials since federal officials participated in the development process. “The feedback we had from them was very positive,” she says.

Karen Pollitz, the deputy director for consumer support in the HHS Office of Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, is one of the officials who will review the materials, says Kammer. Pollitz helped develop the concept of a coverage facts label when she was a research professor at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute.

Pollitz spoke to the working group in September about the idea and co-wrote a report last year that highlighted consumers’ need for better insurance information.

Choosing the wrong policy can have consequences. For example, when comparing breast cancer treatment coverage under three California policies, the study found that a patient would spend nearly $4,000 for a typical treatment under one policy or as much as $38,000 under another even though both policies had similar deductibles and out-of-pocket limits.

“Health insurance should be transparent, so that consumers know what they are getting in a market filled with options that are not always equal,” the researchers concluded.

Susan Jaffe can be reached at jaffe.khn@gmail.com.