Men are dying after opioid overdoses at nearly three times the rate of women in the United States. Overdose deaths are increasing faster among black and Latino Americans than among whites. And there’s an especially steep rise in the number of young adults ages 25 to 34 whose death certificates include some version of the drug fentanyl.

These findings, published Thursday in a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, highlight the start of the third wave of the nation’s opioid epidemic. The first was prescription pain medications, such as OxyContin; then heroin, which replaced pills when they became too expensive; and now fentanyl.

Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that can shut down breathing in less than a minute, and its popularity in the U.S. began to surge at the end of 2013. For each of the next three years, fatal overdoses involving fentanyl doubled, “rising at an exponential rate,” said Merianne Rose Spencer, a statistician at the CDC and one of the study’s authors.

Spencer’s research shows a 113 percent average annual increase from 2013 to 2016 (when adjusted for age). That total was first reported in late 2018, but Spencer looked deeper with this report into the demographic characteristics of those people dying from fentanyl overdoses.

Increased trafficking of the drug and increased use are both fueling the spike in fentanyl deaths. For drug dealers, fentanyl is easier to produce than some other opioids. Unlike the poppies needed for heroin, which can be spoiled by weather or a bad harvest, fentanyl’s ingredients are easily supplied; it’s a synthetic combination of chemicals, often produced in China and packaged in Mexico, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. And because fentanyl can be 50 times more powerful than heroin, smaller amounts translate to bigger profits.

Jon DeLena, assistant special agent in charge of the DEA’s New England Field Division, said 1 kilogram of fentanyl, driven across the southern U.S. border, can be mixed with fillers or other drugs to create 6 or 8 kilograms for sale.

“I mean, imagine that business model,” DeLena said. “If you went to any small-business owner and said, ‘Hey, I have a way to make your product eight times the product that you have now,’ there’s a tremendous windfall in there.”

For drug users, fentanyl is more likely to cause an overdose than heroin because it is so potent and because the high fades more quickly than with heroin. Drug users say they inject more frequently with fentanyl because the high doesn’t last as long — and more frequent injecting adds to the risk of overdose.

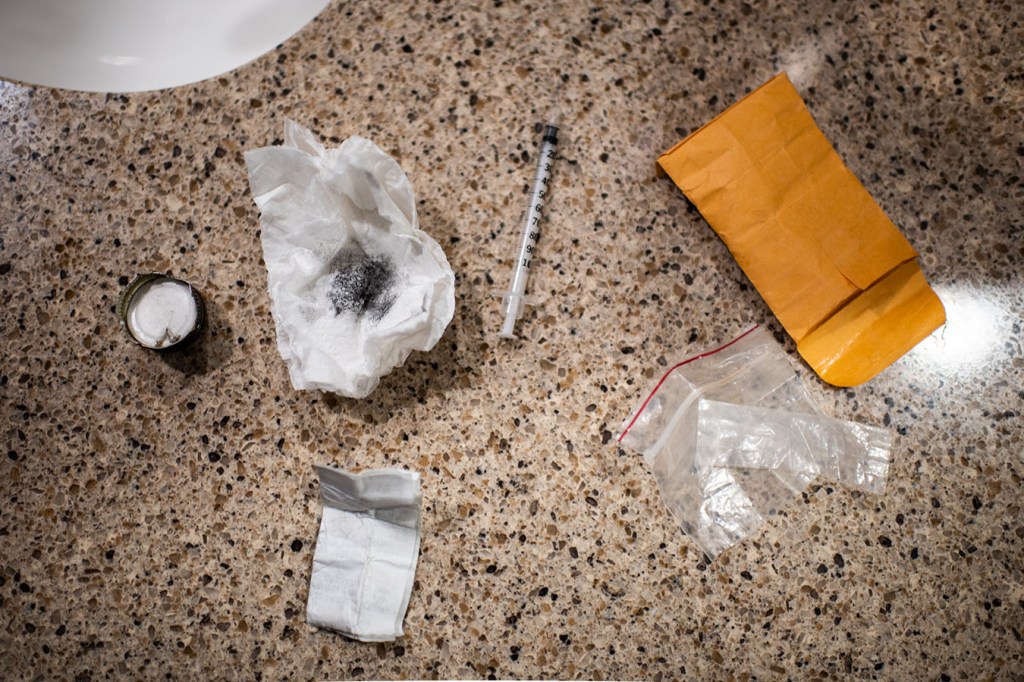

There are several ways fentanyl can wind up in a dose of some other drug. The mixing may be intentional, as a person seeks a more intense or different kind of high. It may happen as an accidental contamination, as dealers package their fentanyl and other drugs in the same place.

Or dealers may be adding fentanyl to cocaine and meth on purpose, in an effort to expand their clientele of users hooked on fentanyl.

“That’s something we have to consider,” said David Kelley, referring to the intentional addition of fentanyl to cocaine, heroin or other drugs by dealers. Kelley is deputy director of the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. “The fact that we’ve had instances where it’s been present with different drugs leads one to believe that could be a possibility.”

The picture gets more complicated, said Kelley, as dealers develop new forms of fentanyl that are even more deadly. The new CDC report shows dozens of varieties of the drug now on the streets.

The highest rates of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths were found in New England, according to the study, followed by states in the Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest. But fentanyl deaths had barely increased in the West — including in Hawaii and Alaska — as of the end of 2016.

Researchers have no firm explanations for these geographic differences, but some experts watching the trends have theories. One is that it’s easier to mix a few white fentanyl crystals into the powdered form of heroin that is more common in Eastern states than into the black-tar heroin that is sold more routinely in the West. Another hypothesis holds that drug cartels used New England as a test market for fentanyl because the region has a strong, long-standing market for opioids.

Spencer, the study’s main author, hopes that some of the other characteristics of the wave of fentanyl highlighted in this report will help shape the public response. Why, for example, did the influx of fentanyl increase the overdose death rate among men to nearly three times the rate of overdose deaths among women?

Some research points to one factor: Men are more likely to use drugs alone. In the era of fentanyl, that increases a man’s chances of an overdose and death, said Ricky Bluthenthal, a professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

“You have stigma around your drug use, so you hide it,” Bluthenthal said. “You use by yourself in an unsupervised setting. [If] there’s fentanyl in it, then you die.”

Traci Green, deputy director of Boston Medical Center’s Injury Prevention Center, offers some other reasons. Women are more likely to buy and use drugs with a partner, Green said. And women are more likely to call for help — including 911 — and to seek help, including treatment.

“Women go to the doctor more,” she said. “We have health issues that take us to the doctor more. So we have more opportunities to help.”

Green noted that every interaction with a health care provider is a chance to bring someone into treatment. So this finding should encourage more outreach, she said, and encourage health care providers to find more ways to connect with active drug users.

As to why fentanyl seems to be hitting blacks and Latinos disproportionately as compared with whites, Green points to the higher incarceration rates for blacks and Latinos. Those who formerly used opioids heavily face a particularly high risk of overdose when they leave jail or prison and inject fentanyl, she noted; they’ve lost their tolerance to high levels of the drugs.

There are also reports that African-Americans and Latinos are less likely to call 911 because they don’t trust first responders, and medication-based treatment may not be as available to racial minorities. Many Latinos said bilingual treatment programs are hard to find.

CDC researcher Spencer said the deaths attributed to fentanyl in her study should be seen as a minimum number — there are likely more that weren’t counted. Coroners in some states don’t test for the drug or don’t have equipment that can detect one of the dozens of new variations of fentanyl that would appear if sophisticated tests were more widely available.

There are signs the fentanyl surge continues. Kelley, with the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, notes that fentanyl seizures are rising. And in Massachusetts, one of the hardest-hit areas, state data show fentanyl present in more than 89 percent of fatal overdoses through October 2018.

Still, in one glimmer of hope, even as the number of overdoses in Massachusetts continues to rise, associated deaths dropped 4 percent last year. Many public health specialists attribute the decrease in deaths to the spreading availability of naloxone, a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose.

This story is part of a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.