Kim had been wine tasting with a friend in Sonoma, Calif. They got into an argument in the car that night and Kim thought someone was following them. She was utterly convinced. And she had to get away.

“I jumped out of the car and started running, and I literally ran a mile. I went through water, went up a tree,” she said. “I was literally running for my life.”

Kim was soaking wet when she walked into a woman’s house, woke her from bed and asked for help. When the woman went to call the police, Kim left and found another woman’s empty guesthouse to sleep in — Goldilocks-style.

“But then I woke up and stole her car,” said Kim, who is 47 and now in recovery. (KHN is using her first name only because she has used illicit drugs.) Kim had been high on Xanax and methamphetamine. “I was crazy. Meth causes people to act completely insane.”

While public health officials have focused on the opioid epidemic in recent years, another epidemic has been brewing quietly, but vigorously, behind the scenes. Methamphetamine use is surging in parts of the U.S., particularly the West, leaving first responders and addiction treatment providers struggling to handle a rising need.

Across the country, overdose deaths involving meth more than quadrupled from 2011 to 2017. Admissions to treatment facilities for meth are up 17%. Hospitalizations related to meth jumped by about 245% from 2008 to 2015. And throughout the West and Midwest, 70% of local law enforcement agencies say meth is their biggest drug threat.

But policymakers in Washington, D.C., haven’t kept up, continuing to direct the bulk of funding and attention to opioids, said Steve Shoptaw, an addiction psychologist at UCLA in Los Angeles, where he hears one story after another about meth destroying people’s lives.

“But when you’re in D.C., where people are making decisions about how to deploy resources, those stories are very much muffled by the much louder story about the opioid epidemic,” he said.

Even within drug treatment circles, there’s a divide. Opioid addiction advocates are afraid their efforts to gain acceptance for measures like needle-exchange programs and safe injection sites will be threatened if meth advocates demand too much.

“The bottom line is, as Americans, we have just so much tolerance to deal with addiction,” Shoptaw said. “And if the opioid users have taken that tolerance, then there’s no more.”

So, lawmakers in San Francisco are trying to get a grip on the toll meth is taking on their city’s public health system on their own. The mayor recently established a task force to combat the epidemic.

“It’s something we really have to interrupt,” said Rafael Mandelman, a San Francisco district supervisor who will co-chair the task force. “Over time, this does lasting damage to people’s brains. If they do not have an underlying medical condition at the start, by the end, they will.”

Since 2011, emergency room visits related to meth in San Francisco have jumped 600% to 1,965 visits in 2016, the last year for which ER data is available. Admissions to the hospital are up 400% to 193, according to city public health data. And at San Francisco General Hospital, of 7,000 annual psychiatric emergency visits last year, 47% were people who were not necessarily mentally ill — they were high on meth.

“They can look so similar to someone that’s experiencing chronic schizophrenia,” said Dr. Anton Nigusse Bland, medical director of psychiatric emergency services at San Francisco General. “It’s almost indistinguishable in that moment.”

They have methamphetamine-induced psychosis.

“They’re often paranoid, they’re thinking someone might be trying to harm them,” he said. “Their perceptions are all off.”

If the person is extremely agitated, doctors might administer a sedative or even an antipsychotic medicine. Otherwise, the treatment is just waiting 12 to 16 hours for the meth to wear off. No more psychosis.

“Their thoughts are more organized, they’re able to maintain adequate clothing. They’re eating, they’re communicating,” Nigusse Bland said. “The improvement in the person is rather dramatic because it happens so quickly.”

Trends In Drug Use Come In Waves

The trend in rising stimulant use is nationwide: cocaine on the East Coast, meth on the West Coast, said Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a professor of medicine and substance use researcher at the University of California-San Francisco.

“It is an epidemic wave that’s coming, that’s already here,” he said. “But it hasn’t fully reached our public consciousness.”

Drug preferences are generational, Ciccarone said. They change with the hairstyles and clothing choices, like bell-bottoms or leg warmers. It was heroin in the 1970s, cocaine and crack in the ’80s. Then opiate pills. Then methamphetamine. Then heroin. And now meth again.

“The culture creates this notion of let’s go up, let’s not go down,” Ciccarone said. “New people coming into drug use are saying, ‘Whoa, I don’t really want to do that. I hear it’s deadly.'”

Kim has been with meth through two waves. When she got into speed in the 1990s, she was hanging out with bikers, going to clubs in San Francisco.

“Now what I see, in any neighborhood, you can find it. It’s not the same as it used to be where it was kind of taboo,” Kim said. “It’s more socially accepted now.”

Dying From Meth

A hint about who uses meth now comes from the data on deaths.

Meth is not as lethal as opioids: 47,600 people died of opioid-related overdoses in 2017 compared with 10,333 deaths involving meth. But the death rate for meth has been rising. Meth-related deaths in San Francisco doubled since 2011, another indication that more people are using meth and that today’s supply is very potent, said the UCSF’s Ciccarone.

Another hypothesis to explain the growth in meth-related overdoses is that meth users are aging. Most meth deaths are from a brain hemorrhage or a heart attack, which would be unusual for a 20-year-old.

“Because your tissue is so healthy at that age,” said Dr. Phillip Coffin, a physician and the director of substance use research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health. “Whereas when you’re 55 years old and using methamphetamine, you might be at higher risk for bursting a vessel and bleeding and dying from that.”

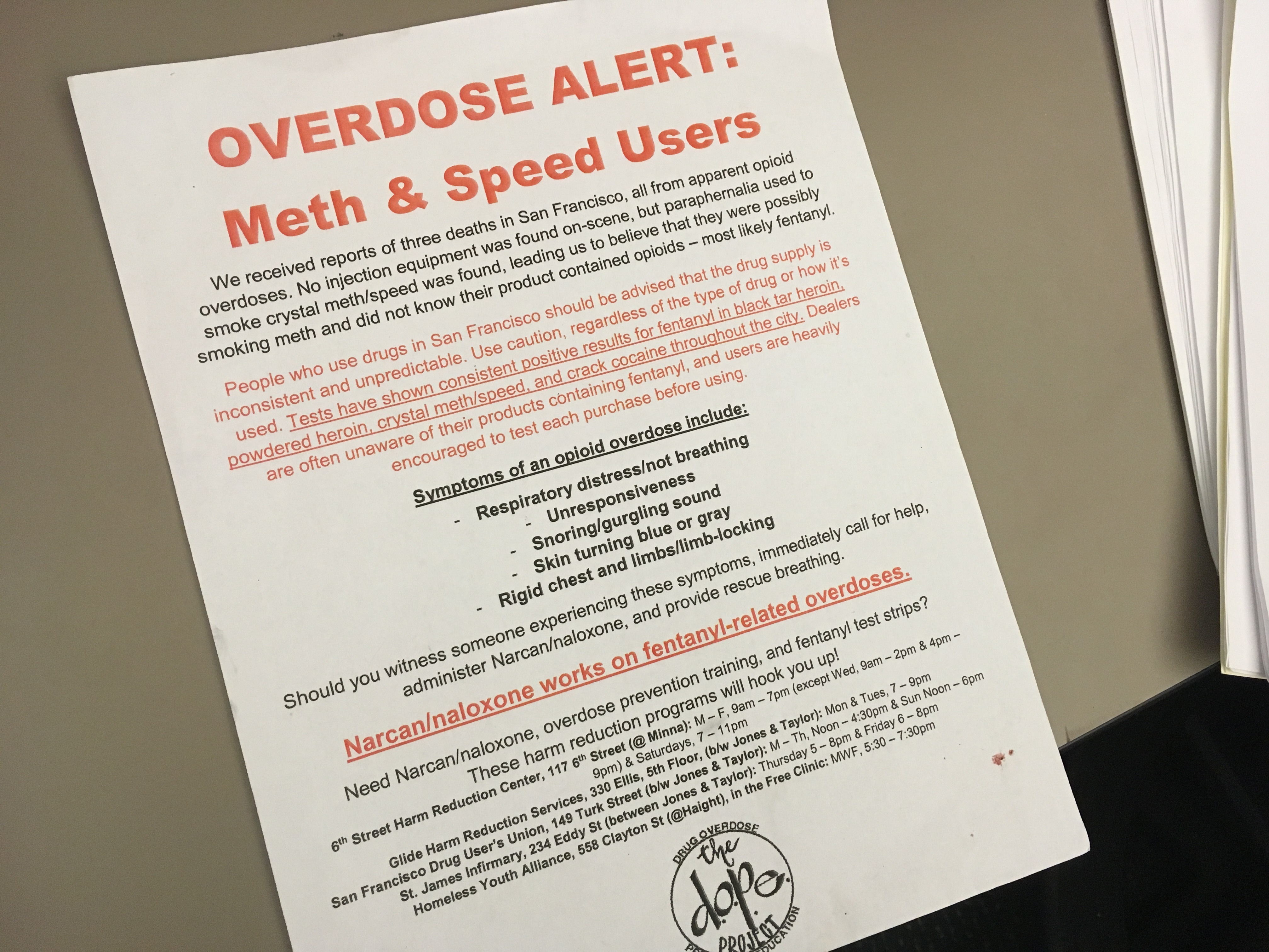

Another explanation for the rising death rate is that meth has become contaminated. And that affects everyone, old and young. Last year, three young people in San Francisco died after smoking meth together. It turns out the meth had fentanyl in it. The synthetic opioid has been causing waves of heroin overdoses across the country, but now it’s showing up mixed into cocaine and meth.

Most researchers believe the contamination happens accidentally, when a dealer uses the same equipment to bag fentanyl and later meth, Ciccarone said.

A meth overdose alert from the Drug Overdose Prevention and Education Project.(April Dembosky/KQED)

Relapses Are Common

Over her two decades of meth use, Kim has been through drug treatment more than a dozen times. Relapse is part of recovery, and among meth users, 60% will start using again within a year of finishing treatment. Unlike opioids, there are no medication treatments for meth addiction, which makes it particularly hard to treat.

In April, Kim completed a six-month residential treatment program for women in San Francisco called the Epiphany Center. She came directly from jail, after serving time for her housewarming-and-car-theft spree in Sonoma. She said that in the first 30 days all she could do was try to clear the chaos from her mind.

“You have to get used to sitting with yourself, which is essential for life, is to get along with your own self,” she said.

Kim, who has four children, is hopeful that this round of treatment will stick. She is living in transitional housing now, has a job and has been accepted to a program at the University of California-Berkeley to finish her college degree.

“I’ve gone through 12 different programs and it’s been for my children, for my mom, for the courts. I’ve never come to be there for myself,” Kim said. “So it’s like I’ve come to a place where it has to be for me.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes KQED, NPR and Kaiser Health News.