The Trump administration’s decision to alter the way it punishes nursing homes has resulted in lower fines against many facilities found to have endangered or injured residents.

The average fine dropped to $28,405 under the current administration, down from $41,260 in 2016, President Barack Obama’s final year in office, federal records show.

The decrease in fines is one of the starkest examples of how the Trump administration is rolling back Obama’s aggressive regulation of health care services in response to industry prodding.

Encouraged by the nursing home industry, the Trump administration switched from fining nursing homes for each day they were out of compliance — as the Obama administration typically did — to issuing a single fine for two-thirds of infractions, the records show.

That reduces the penalties, giving nursing homes less incentive to fix faulty and dangerous practices before someone gets hurt.

“It’s not changing behavior [at nursing homes] in the way that we want,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, a professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “For a small nursing home it could be real money, but for bigger ones it’s more likely a rounding error.”

Since Trump took office, the administration has heeded multiple nursing home complaints about zealous oversight. It granted facilities an 18-month moratorium from being penalized for violating eight new health and safety rules. It also revoked an Obama-era rule barring homes from pre-emptively requiring residents to submit to arbitration to settle disputes rather than go to court.

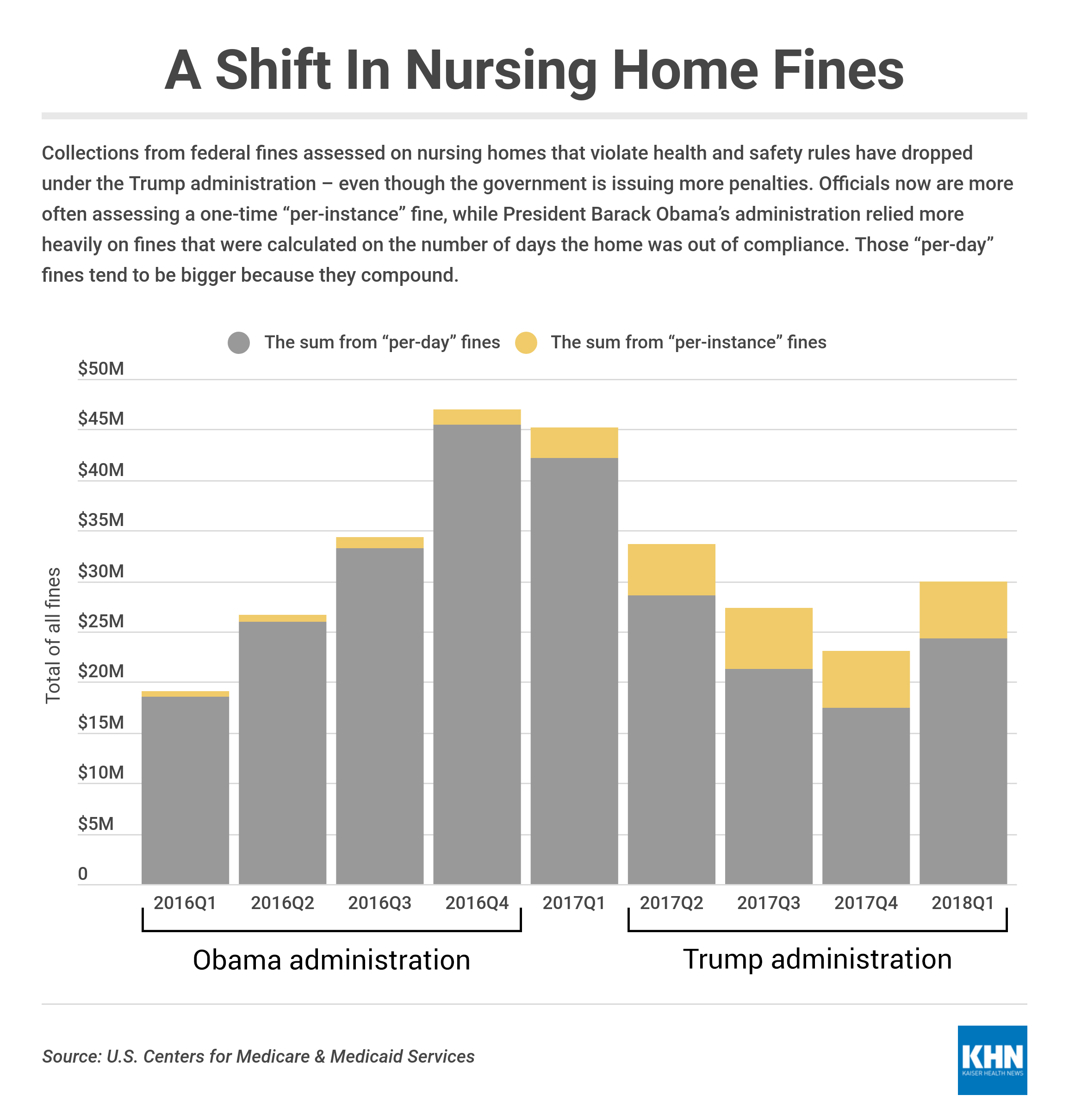

The slide in fines occurred even as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued financial penalties 28 percent more frequently than it did under Obama. That’s due to a policy begun near the end of Obama’s term that required regulators to punish a facility every time a resident was harmed, instead of leaving it to their discretion.

While that policy increased the number of smaller fines, larger fines became less common. The total amount collected under Trump fell by 10 percent compared with the total in Obama’s final year, from $127 million under Obama to $114 million under Trump. (KHN compared penalties during 2016, Obama’s last year in office, with penalties under Trump from April 2017 through March 2018, the most recent month for which federal officials say data is reliably complete.)

(Story continues below.)

CMS said it has revised multiple rules governing fines under both administrations to make its punishments fairer, more consistent and better tailored to prod homes to improve care. “We are continuing to analyze the impact of these combined events to determine if other actions are necessary,” CMS said in a statement.

The move is broadly consistent with the Trump administration’s other industry-friendly policies in the health care sector. For instance, the administration has expanded the role of short-term insurance policies that don’t cover all types of services, given states more leeway to change their Medicaid programs and urged Congress to allow physicians to open their own hospitals.

Beth Martino, a spokeswoman for the American Health Care Association, a nursing home trade group, said the federal government has “returned to a method of applying fines in a way that incentivizes solving problems” rather than penalizing “facilities that are trying to do the right thing.”

Penalty guidelines were toughened in 2014, when the Obama administration instructed officials to favor daily fines. By 2016, those were used in two-thirds of cases. Those fines averaged $61,000.

When Trump took over, the nursing home industry complained that fines had spun “out of control” and become disproportionate to the deficiencies. “We have seen a dramatic increase in [fines] being retroactively issued and used as a punishment,” Mark Parkinson, president of the nursing home group, wrote in March 2017.

CMS agreed that daily fines sometimes resulted in punishments that were determined by the random timing of an inspection rather than the severity of the infraction. If inspectors visited a home in April, for instance, and discovered an improper practice had started in February, the accumulated daily fines would be twice as much as if the inspectors had come in March.

But switching to a preference for per-instance fines means much lower penalties, since fines are capped at $21,393 whether they are levied per instance or per day. Homes that pay without contesting the fine receive a 35 percent discount, meaning they currently pay at most $13,905.

Those maximums apply even to homes found to have committed the most serious level of violations, which are known as immediate jeopardy because the home’s practices place residents at imminent risk of harm. For instance, a Mississippi nursing home was fined $13,627 after it ran out of medications because it had been relying on a pharmacy 373 miles away, in Atlanta. CMS also reduced $54,600 in daily fines to a single fine of $20,965 for a New Mexico home where workers hadn’t been properly disinfecting equipment to prevent infectious diseases from spreading.

On average, per-instance fines under Trump were below $9,000, records show.

“These are multimillion businesses — $9,000 is nothing,” said Toby Edelman, a senior policy attorney at the Center for Medicare Advocacy, a nonprofit in Washington.

Big daily fines, averaging $68,080, are still issued when a home hasn’t corrected a violation after being cited. But even in those cases, CMS officials are allowed to make exceptions and issue a single fine if the home has no history of substantial violations.

The agency cautioned that comparisons of average fines is misleading because the overall number of inspections resulting in fines increased under Trump, from 3.5 percent in 2016 to 4.7 percent. The circumstances now warranting fines that weren’t issued before tend to draw penalties on the lower side.

However, KHN found that financial penalties for immediate jeopardies were issued in fewer cases under Trump. And when they were issued, the fines averaged 18 percent less than they did in 2016.

The frequency of immediate-jeopardy fines may further decrease. CMS told inspectors in June that they were no longer required to fine facilities unless immediate-jeopardy violations resulted in “serious injury, harm, impairment or death.” Regulators still must take some action, but that could be ordering the home to arrange training from an outside group or mandating specific changes to the way the home operates.

Barbara Gay, vice president of public policy communications at LeadingAge — an association of nonprofit organizations that provide elder services, including nursing homes — said that, under Trump, nursing homes “don’t feel they’ve been given a reprieve.”

But consumer advocates say penalties have reverted to levels too low to be effective. “Fines need to be large enough to change facility behavior,” said Robyn Grant, director of public policy and advocacy at the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, a nonprofit based in Washington. “When that’s not the case and the fine is inconsequential, care generally doesn’t improve.”